Artistic works inspired by the Great Famine struggle to do it justice, but they keep the memory alive

The Famine Memorial in Dublin, by sculptor Rowan Gillespie. (opens in a new window)Ron Cogswell, (opens in a new window)CC BY

Posted 14 November, 2018

(opens in a new window)Emily Mark-FitzGerald, (opens in a new window)University College Dublin

How do you represent in film an experience as keen and painful as hunger? Director Lance Daly’s recently released film (opens in a new window)Black ‘47 – a revenge epic set during the 1840s Irish famine – is the latest attempt to depict the devastating catastrophe which left more than a million dead in Ireland in one of the worst episodes of human suffering in the 19th century. The famine’s legacy is profound: today Ireland remains the only European country with a smaller population than in the 1800s.

(opens in a new window) Robert Fripp’s ‘An Irish Peasant and her Child’, a saccharine portrait of curiously well-fed looking victims of the famine. (opens in a new window)Robert Fripp/Ireland's Great Hunger Museum

Robert Fripp’s ‘An Irish Peasant and her Child’, a saccharine portrait of curiously well-fed looking victims of the famine. (opens in a new window)Robert Fripp/Ireland's Great Hunger Museum

Yet the problem of how (and whether) to convey the horrors of the famine in visual art perplexed artists of the period. There were few conventions in Victorian art practice to represent the starving human body in extremis. More commonly, paintings of the famine reverted to saccharine images of noble peasants at the mercy of external forces, or caricatures of Irish indolence and fecklessness, or simply ignored the crisis altogether, since it didn’t accord with the values or interests espoused by academic painting.

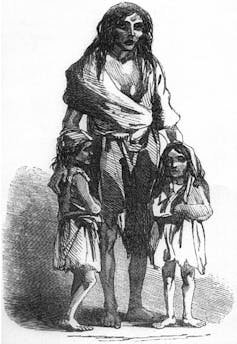

Illustrated journalism – which was in its infancy, with the Illustrated London News founded only in 1842 – fared somewhat better. Many of the best-known depictions of the famine are from journalistic coverage of the crisis, such as the sketch of (opens in a new window)Bridget O'Donnel and Children from the Illustrated London News, December 22 1849. Black ‘47 makes ample use of this source material, with its opening sequences explicitly mimicking the monochrome palette of 1840s wood engraving.

The sketch accompanying the story of Bridget O'Donnel in the Illustrated London News has become one of the best-known depictions of the famine. (opens in a new window)Illustrated London News

The sketch accompanying the story of Bridget O'Donnel in the Illustrated London News has become one of the best-known depictions of the famine. (opens in a new window)Illustrated London News

But newspaper coverage was uneven, as what they published was also constrained by their perception of what readers would tolerate. Although frequently based on eyewitness accounts, newspaper images generally pale in comparison with the words that accompany them: too shocking an image and the viewer would quickly turn the page.

Did a silence descend upon Britain and Ireland on the subject in the aftermath of the famine? Has it really remained an unspoken horror left in the past? (opens in a new window)Recent research on the visual and textual representation of the famine challenges this broad view. Today scholars of “famine memory” seek to more closely observe when, and crucially why, the famine emerges or shifts as a subject of representation. Far from being an unrepresentable event, the memory of the famine has assumed a wide array of visual and textual forms from the 19th century to the present. These include popular and literary fiction, drama, political rhetoric, print and painted depictions, photography and film.

Touted as the “first famine film”, Black ’47 is intriguing example of the genre, but not the first. That distinction belongs to the silent film Knocknagow (1918), the first feature entirely shot and produced in Ireland by the Film Company of Ireland, set loosely during the famine period and based on (opens in a new window)the popular 1873 novel by Charles Kickham.

With a sentimental and convoluted storyline combining star-crossed lovers, forced emigration, an absentee landlord and a rapacious land agent, and with a dramatic centrepiece scene depicting an eviction, Knocknagow drew upon stock characters and vignettes with broad appeal to the anticipated (largely American) audience. It used a repertoire of images of famine and eviction well known to contemporary audiences through their repetition in decades of painting, engraving and in popular fiction.

Black ’47 adopts many of these same elements, but its dramatic action is situated in the genre of the revenge western (a kind of O’(opens in a new window)Django Unchained), and it offers a far more sophisticated telling of a familiar story. For example, the targets of its central character’s fury range from the indifferent landlord, a frequent villain in 19th and 20th-century famine fiction, to the (opens in a new window)gombeen-man, a complex figure who exploited the suffering of his own people (and in the film, his own family).

During the 150th anniversary of the famine in the 1990s, hundreds of public memorials were constructed across Ireland and in the new homelands of the expansive Irish diaspora, something I discuss in (opens in a new window)Commemorating the Irish Famine: Memory and the Monument. Public interest shows no sign of waning since: new memorials are planned, from Glasgow to San Francisco, and the Irish government has adopted an annual (opens in a new window)National Day of Famine Commemoration. Nevertheless, all representations of the famine respond to pre-existing literary or visual traditions, are crafted to appeal to specific viewers, and stem from a range of political and social motivations. As such, any image of the famine is a complex artefact of its own time and place, not merely an illustration or reflection of historical experience or collective cultural memory.

Since the 19th century people have questioned whether the famine is a suitable subject for creative reinterpretation. Howls of (opens in a new window)outrage greeted news of Hugh Travers’ “famine sitcom” pilot commissioned by Channel 4 in 2015, a project eventually abandoned. But the famine should not be considered any kind of sacred cow: this has certainly never been the case historically. As the genealogy of its depiction shows us – from (opens in a new window)The Black Prophet by William Carleton, writing at the time of the famine, to Black ’47 today, the seismic shock of the famine has continued to haunt all subsequent generations, each seeking forms of comprehension and meaning.

As Walter Benjamin (opens in a new window)observed: “To articulate what is past does not mean to recognise ‘how it really was’. It means to take control of a memory, as it flashes in a moment of danger.” The making, and remaking, of the famine will recur so long as its memory unsettles us.

(opens in a new window)Emily Mark-FitzGerald, Associate Professor in the School of Art History and Cultural Policy, (opens in a new window)University College Dublin

This article is republished from (opens in a new window)The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the (opens in a new window)original article.

![]()