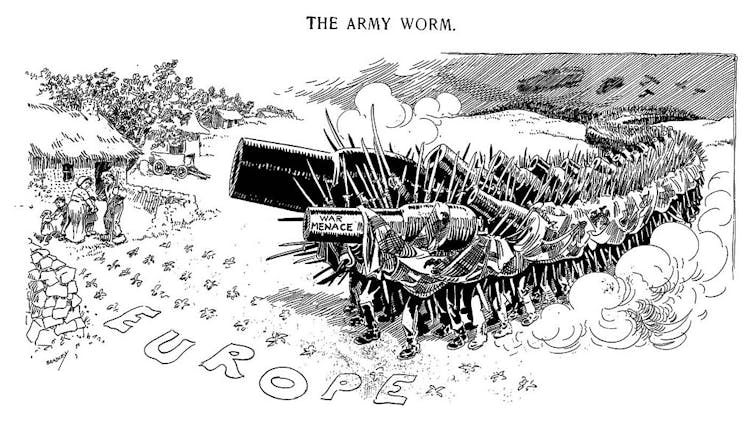

Opinion: When political leaders choose catastrophe - how Europe walked willingly into World War I

Posted 22 February, 2019

(opens in a new window)William Mulligan, (opens in a new window)University College Dublin

Some political catastrophes come without warning. Others are long foretold, but governments still walk open-eyed into disaster. As the possibility of a no-deal Brexit looms, most analysts agree that there will be (opens in a new window)severe economic and political consequences (opens in a new window)for the UK and the EU. And yet a no-deal Brexit still remains an option on the table.

The July crisis in 1914 that lead up to World War I, which I’ve analysed (opens in a new window)in a recent paper, provides a timely case study of how politicians chose a catastrophic path. World leaders knew that that a European war would most likely bring economic dislocation, social upheaval, and political revolution – not to mention mass death – but they went ahead anyway. Far from thinking that the war would be short – “over by Christmas” as the (opens in a new window)cliché goes – leaders across Europe shared the view expressed by the British chancellor, David Lloyd George that war would be “armageddon”.

So why did European leaders not swerve away from catastrophe in 1914? A toxic mix of wishful thinking, brinksmanship, finger-pointing, and fatalism – features currently increasingly evident in the Brexit dénouement – conspired to make the risk of catastrophic war appear a legitimate, even rational, option.

First, a small number of leaders, mainly generals, believed that war would cleanse society of its materialist and cosmopolitan values. The more terrible the consequences, the more effective the war would be in achieving national renewal. War, they argued, would bolster the values of self-sacrifice and cement social cohesion. Instead, material shortage led to (opens in a new window)military defeat and social disintegration in Russia, Austria-Hungary and Germany.

Second, some politicians believed that the prospect of catastrophe could be used to lever their opponents into concession. Kurt Riezler, adviser to the German chancellor Bethmann Hollweg, had coined the term Risikopolitik, or risk policy. He predicted that, faced with the possibility of a European war, the great powers with less at stake would back down in any given crisis. But this logic broke down if both sides considered their vital interests in danger and if both sides faced similarly catastrophic consequences from war. This led to absurdities in the July crisis, such as the (opens in a new window)comment from Germany’s Kaiser William II that: “If we should bleed to death, at least England should lose India.”

Shifting blame

Third, politicians framed the crisis as a choice between two catastrophes. If they backed down, they feared the permanent loss of status, allies, and, ultimately, security. For Austro-Hungarian leaders, compromise rendered them vulnerable to further Serbian provocations and the slow disintegration of the Habsburg empire. War became the lesser of two evils, a highly risky strategy that might, but probably would not, avert certain ruin. As states began to mobilise, military and political leaders feared that whichever side moved first could gain a significant military advantage. Waiting too long risked the dual catastrophe of being at war and suffering an initial defeat. This logic was particularly important in the spiral of mobilisation on the eastern front, between Austria-Hungary, Russia and Germany.

Fourth, as war became increasingly likely, leaders began to deny their own ability to resolve the conflict. Politicians began to allocate blame for the coming conflict on their opponents. Lloyd George, who went on to become prime minister in 1916, later famously claimed that Europe had (opens in a new window)“slithered” into war. The denial of agency encouraged the sense of fatalism that facilitated the outbreak of war. If leaders perceived war as inevitable, this inevitability made it psychologically easier to accept the appalling consequences.

Fifth, individual decisions, such as allies assuring their unfailing loyalty to their partners, were often intended to avoid war by forcing the other side to back down. Yet, instead of making concessions, states doubled down on their demands and stood full-square by their allies, without urging compromise. The outcome was the rapid escalation of the crisis into war.

Seasoned diplomats at the helm

Most of the key diplomats in July 1914 had recently resolved major international crises, notably during the Moroccan Crisis in 1911 and the remaking of the Balkans during regional wars in 1912 and 1913. They had the diplomatic skills to avoid disaster.

Yet, by framing the July crisis in terms of an existential test – of status, territorial integrity, and the value of alliances – leaders in all the great powers trapped themselves in a spiral of escalating tensions and decisions. This meant they began to rationalise war as a possible option from early July.

Although the consequences of a no-deal Brexit will be much less terrible, there are similarities in certain patterns of thinking and political behaviour, from the few who embrace disaster to the systemic pressures which prevent compromise. Avoiding disaster in 1914 would have required framing the stakes of the July crisis in less zero-sum ways and refusing to rationalise a general European war as an acceptable policy option. It required leaders with enough courage to compromise, even to accept defeat, and for states to offer rivals the prospect of long-term security and future gains in exchange for accepting short-term setbacks.

(opens in a new window)William Mulligan, Professor, School of History, (opens in a new window)University College Dublin

This article is republished from (opens in a new window)The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the (opens in a new window)original article.

![]()