The children of today will be among the first few generations who will face a world with increasing climate uncertainties and depleted biodiversity and nature. The primary focus of this research was to better understand children’s knowledge of and views on climate change and nature and consequently develop strategies to address any knowledge deficits, says UCD Masters graduate Georgina Fagin.

Climate change is one of the greatest threats that humanity faces, but how do children understand and cope with these uncertainties? One of the critical starting points of climate change education is to understand how children perceive nature. Children today spend less time outdoors. This lack of outdoor engagement is leading to a culture of environmental apathy and separation from the natural world. This concern has only been compounded over the past two years, with the COVID-19 crisis resulting in people spending more time inside. In addition, lifestyles have become considerably more urbanised. As a result of this urbanised lifestyle, there are fewer natural places, there is a focus on car culture, increased screen time and time spent indoors, and increased time pressures from school. Consequently, there has been a decrease, or even elimination, of contact with nature.

Climate change is one of the greatest threats that humanity faces, but how do children understand and cope with these uncertainties? One of the critical starting points of climate change education is to understand how children perceive nature. Children today spend less time outdoors. This lack of outdoor engagement is leading to a culture of environmental apathy and separation from the natural world. This concern has only been compounded over the past two years, with the COVID-19 crisis resulting in people spending more time inside. In addition, lifestyles have become considerably more urbanised. As a result of this urbanised lifestyle, there are fewer natural places, there is a focus on car culture, increased screen time and time spent indoors, and increased time pressures from school. Consequently, there has been a decrease, or even elimination, of contact with nature.

Research conducted to understand how children in Ireland perceive nature shows interesting trends. For example, my research on 12–14-year-olds instructed to draw a picture of what came to mind when they thought about nature found that children drew more trees to signify nature. Other life forms like animals or types of landscapes like vast open peatlands or water bodies thriving with life were largely missing. Another finding that emerged was a distinct lack of humans in the drawings. Only five drawings featured humans in some capacity, with only one drawing depicting the destruction of nature by humans. Such findings suggest that human beings are separate from nature rather than being part of it. Even when they are part of nature, humans are construed as playing the role of destruction.

Drawings made by the students aged 12-14

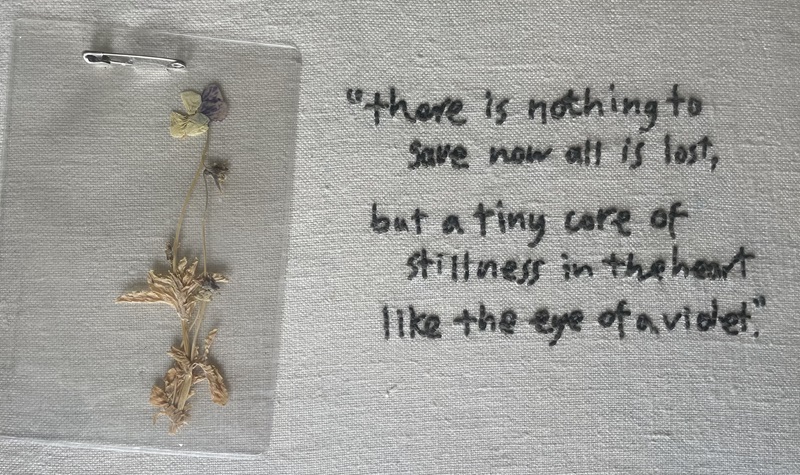

When questioned on what climate change means, the children’s most popular answers were changes to the climate, weather, temperature, and presence of gases. This displays a good understanding of the impacts of climate change on temperature and weather, for example, but very few children made references to anthropogenic drivers. Children displayed an understanding of the popular narrative of climate change which they may have learned in school, at home or online but they do not grasp the full meaning of it. However, understanding climate change in terms of weather patterns and temperature rise problematises how children can cope with climate anxiety. A sense of helplessness pervades especially with the status of the earth they have inherited and in the words of one participant:

“Young people often blame our parents’ generation for climate change… and they’re the ones who allowed all of the heavy carbon emissions to start and not protest like we are now. We find it unfair that elders blame the youth of today for climate change when this was simply the world we were born into and didn’t have a say in it.”

What this points towards is that climate change education is important for children to help them understand anthropogenic drivers of climate change better. Early adolescence is an extremely important time in the formation of attitudes related to climate change and to build their agency to mitigate and adapt to it. Educating children at the right age on the different aspects of climate change adaptation and mitigation have multiple long-term benefits like making them conscious about their lifestyle choices, increase their ability to cope with climate grief and anxiety that is increasingly being noticed in young people and foster climate concern in parents.

Essay first published 19 April 2022.

About the author

Georgina Fagan completed a Master’s degree in Environmental Sustainability in UCD during the academic years 2019-2021. Georgina is a practising post primary school teacher of Science and Physical Education in County Dublin, Ireland. As part of her Master’s degree, she conducted a research study in relation to children aged 12-16 on their views of climate change and nature under the direction and guidance of Associate Member Dr. Aparajita Banerjee.

About the series

The A-Z of Environmental, Climate and Sustainability Research is a new series of short essays by UCD postdoctoral and postgraduate researchers, technical and research support staff, about their work. The series is developed and curated by the Earth Institute Associate Member Committee led by Hannah Gould, a PhD student at BiOrbic and the UCD School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Policy, and Earth Institute Communications and Engagement Officer Liz Bruton. If you'd like to submit a piece for the series do get in touch!

Find out more about the Anthropocene with Nick Scroxton, Bees with Katherine Burns, Cannabis with Caroline Dowling, Degrowth with Ciarán O'Brien, Education with Georgina Fagan, Finance with Shane McGuinness, Gaia with Federico Cerrone, Hydrometry with Kate de Smeth, Innovation with Hannah Gould, Justice with Lauren Minion, Kelp with Priya Pollard, Landscape part 1 with Tomas Buitendijk, Landscape part 2 with Amy Strecker and Amanda Byer, Reusing microbial ‘bathwater’ for sustainable drug production with Laura Murphy, and Mammals with Virginia Morera-Pujol in our latest essays.

Further reading

Kahn, P.H. & Weiss, T. (2017) The Importance of Children Interacting with Big Nature. Children, Youth and Environments 27(2), 7-24.

Ojala, M. (2012) Regulating Worry, Promoting Hope: How Do Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults Cope with Climate Change?. International Journal of Environmental and Science Education 7(4), 537-561.

Ojala, M. (2012) How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. Journal of Environmental Psychology 32(3), 225-233.