The relationship between climate change and agriculture is a contentious, complex and important one. In this series of thirteen blogs, UCD Adjunct Professor Frank Convery will explore the context, challenges and potential solutions for dairy, beef and sheep farming in Ireland. Each blog presents key evidence to underpin informed debate and the series seeks to help plot a sustainable future for the sector.

Professor Eoin O'Neill, Director, UCD Earth Institute

12. Climate Performance by Irish Ruminant Farming: New policies to drive emissions reductions and carbon removal at scale

Frank Convery, Adjunct Professor, University College Dublin

How to cite this blog (APA): Convery, F. (2023, October 17). Climate Performace by Irish Ruminant Farming: New policies to drive emissions reductions and carbon removal at scale. UCD Earth Institute Climate Policy for Ruminant Agriculture in Ireland. https://www.ucd.ie/earth/blog/climate-policy-agriculture-ireland-blog/climatepolicyforruminantagricultureinirelandblog12/.

See https://libguides.ucd.ie/academicintegrity on how to cite in other formats.

“Ireland will become a world leader in Sustainable Food Systems (SFS) over the next decade. This will deliver significant benefits…and will also provide the basis for the future competitive advantage of the sector”.

Food Vision 2030 [1]

“The deep connection that has always existed between our people and the land has translated into a commitment to fight climate crisis to preserve our planet for future generations. The single existential threat to the world is climate change. We don’t have a lot of time, and that’s a fact. Ireland’s famous 40 shades of green are being supplemented by green energy, green agriculture, green jobs….. Our world stands at an inflection point where the choices we make today are literally going to determine the future of the history of this world for the next four to five decades — literally, not figuratively”.

President Joe Biden, to the Oireachtas, April 13, 2023. [2]

Key Points

- The new normal is this: If Irish ruminant farming doesn’t perform to high climate and environmental standards, there will be negative commercial consequences and spurious claims will be illegal.

- We failed to deliver on the commitment in Food Wise 2025 published in 2015 that “Environmental protection and economic competitiveness are equal and complementary: one will not be achieved at the expense of the other.” The consequence was that as farming intensified, nitrate pollution increased in 9 catchments and water quality deteriorated. The core compliance requirement under which some farmers were given a derogation allowing them to spread 250 Kg of manure/ Ha (the standard allowance is 170 Kg/Ha) is the 6-word condition of the Nitrates Directive - “will not contribute to higher pollution.” It did, and now the derogation will be reduced to 220 Kg/Ha. This will add to costs. It is likely that unless the deterioration in the water quality in 9 catchments is reversed, the derogation will be removed completely at the next review, and this will add even more to on-farm costs. There are no free lunches here.

- Increasing carbon footprint competition (Kgs CO2e/Kg of product) from dairy beef and sheep farmers producing in our top three markets (EU, UK, US) is in prospect. Within the EU, in 2018, France initiated a programme to encourage carbon removal and emissions reduction and the labelling of achievement in this regard, with a particular focus on forestry and farming Low-carbon label: rewarding actors in the fight against climate change [| Ministries Ecology Energy Territories (ecologie.gouv.fr)] and in Denmark a Working Group has recently made recommendations in regard to carbon labelling of food. California started to support the reduction in greenhouse gas emissions in 2015, by inviting their dairies and farmers to apply competitively for grant aid to reduce their emissions, evaluated as follows: 50% of the marks based on emissions reduced, and the other 50% for the technical quality credibility and cost effectiveness (value for money) of the proposals to do so. Digester projects are also able to receive environmental credits under the state’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) Program and the federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) Program. At US federal level, in the range of €9.5 billion to €20 billion are provided via the Inflation Reduction Act (2022) to support farmers make climate smart investments. Similar investment support (ELMS) is beginning to flow to farmers in England and Wales, and increasingly carbon efficient product from NZ and Australia will have tariff-free access to this market. The choices of some premium customers in these three markets will be influenced by their understanding of the Kgs of CO2 emissions associated with their purchases. We will start leaking premium customers in these markets if we do not match this competition. When launching New Zealand’s climate strategy for farming, Minister for Agriculture put climate competitive front and centre of his case for action: The heading was ‘New Emissions Plan will Future Proof New Zealand’s Export sector’, and he observed that: “Nestle, the single biggest customer of our biggest company, Fonterra, has committed to a 50 per cent reduction of scopes 1, 2 and 3 emissions by 2030. Many more companies have similar targets. This is a tectonic shift in our export markets, meaning our farmers will have to reduce their emissions in order to sell to them” https://www.beehive.govt.nz/release/new-emissions-reduction-plan-will-future-proof-nz%E2%80%99s-largest-export-sector. As you know, New Zealand now has tariff free access to the UK market.

- There are two recent EU developments of huge significance, that have gone relatively unremarked in the public domain: The first is the requirement in the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive that Scope 3 emissions, i.e., those that are farm-based, be included in reporting; the second is the so called ‘Greenwashing’ Directive, which will prohibit spurious climate and environmental claims. Both credible measurement and penalties for erroneous green claims are two new realities for the Irish food industry and Irish farmers.

- The sector also desperately needs ‘public goods’ success, defined as greenhouse emissions removed and carbon stored at scale, clean river catchments and vibrant nature especially around land-based Natura 2000 sites, for other reasons:

- Without it, the debilitating and psychologically destructive drum beat of media criticism will continue and is likely to grow as climate change impacts intensify in real time; the status of the profession falls, and succession challenges increase.

- With it, criticism evolves to admiration and disparagement is replaced by praise.

- There has been important policy progress in Ireland including: development and presentation of evidence by Teagasc on many fronts; regulation supporting progress on nitrates reduction, including imposing requirements – e.g., Low Emissions Slurry Spreading (LESS) to qualify for derogation; large increase in climate-environment spending (funded by revenues generated by the carbon tax) in CAP 2023-2027; impressive developments in: on-farm emissions’ measurement - Gerry Boyle: 'When it comes to carbon, you can’t manage what you don’t measure' - 09 August 2023 Premium (farmersjournal.ie); the actions of some courageous farmers (Signpost farmers etc.); the integration of clover and mixed swards, and developments in methane reducing genetics and farm demonstration; the coherence of the recommendations of the Food Vision Dairy and Beef groups; actions by coops and others and Bord Bia/Origin Green on bonus payments, rapid rise in membership of SDAS and SBLAS.

- But this progress will not be anything like enough to ensure success and the reasons are simple:

- Because of the huge average income gap between dairy farming and cattle and sheep farming in Ireland, there is an understandable inclination in the design and delivery of climate and other policies to favour using the funding to help narrow the income gap. Pillar 1 (basic income) funded 100% by the Commission is a zero-sum game. The total amount is fixed, 130,000 farmers are beneficiaries, and if group A get more, then the rest must get less. It is a zero-sum game, and this makes the politics toxic.

- Pillar 2 (Rural Development) is co-funded, and this is where the main climate-environment support - ACRES in CAP 2023-2027 – comes from. The de facto main criterion for success is number of farmers participating, and this means spreading the money widely but thinly.

- There is not a mission focus on magnitude and quality of outcomes in terms of: greenhouse gas emissions reduced and carbon stored, number of river catchments whose water quality is conserved and improved, or the number of Natura 2000 sites whose habitats are protected and species restored.

- Future success will require designing and delivering policies that deliver these three missions.

- Except for policies that emerged in CAP 2014-2020 from the European Innovation Projects to protect nature, our current portfolio is not designed to succeed in these terms.

- Because of the equity and political constraints noted above, it will be impossible to change policies and outcomes within the current CAP framework. New policies and new money will be required.

- This will require changes in policy and evolution in the all-of-government approach: Specifically:

- Policies that have a laser-like focus: discover where the best opportunities lie; directly incentivise outcomes at scale and delivering value for money (there are lessons on all three from California); climate and water quality improvement policies in some geographies are integrated to maximize synergies; accelerate progress on those Natura 2000 sites where payoff to effort is greatest, and remove the cap on payments - the focus here is on outcomes, not income support; mobilize innovation to widen and deepen choices and lower costs - we have made some good progress with R&D and demonstration, but see Blog 11 Innovation for thoughts on the other essential elements of a mission focussed innovation strategy that need addressing.

- Five departments – Taoiseach (integration and barrier removal) Finance (funding and tax expenditure instruments) Expenditure and Reform (value for money), Environment Climate and Communications (climate strategy) and Agriculture Food and Marine (Implementation) - are essential for the design and execution of policies that deliver outcomes at scale in ways that are value for money.

- Three departments and their agencies - Housing Local Government and Heritage (water quality and Natura 2000 priorities), Environment Climate and Communications (climate priorities) and Agriculture Food and Marine (implementation) – are essential for the coherent and efficient integration of policies at river catchment level.

- Five other departments also have key roles – Foreign Affairs (bridge in real time to developments in key markets on climate-relevant technical and policy developments and consumer preferences); Rural and Community Affairs (Rural Action); Further and Higher Education Research and Innovation (Innovation strategy); Enterprise Trade and Employment (special support for companies excelling via Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive and helping avoid non-compliance with the Greenwashing Directive); Tourism Culture Arts Gaeltacht and Media (Emotion matters).

- Miscellaneous

The absence of an effective farmer lobby for policies that would deliver climate, water quality and nature conservation policies at scale that are cost-effective limits their prospects of being delivered. Unless they emerge, it will be difficult to succeed. For this reason, my final blog 13 (Farmers) is directed to farmers, in hopes that a significant minority will recognize that their commercial future and that of their successors is likely to be bleak unless they fight for policy change along the lines I outline.

How much money would it take to drive the change above? I have no idea how much will be needed, and there will be learning by doing as we proceed. The important words are value for money. If, and only if this is assured, then we need to spend whatever it takes, and it would be far better to spend nothing than to devote new money in ways that fail. The roles of Finance and DEPR are essential here, but for some context I note that €5 billion over 10 years (€500 million) is allocated from carbon tax revenues by the current government to drive emissions reduction from housing, and that 4% of our global export revenues of €10 billion generated by ruminant farming in 2022 is €400 million.

My only information on DAFM’s cow cull proposal comes from Farming Independent, May 30, 2023 - Revealed: €600m budget needed to cull 65,000 cows every year for three years to meet climate goals | Independent.ie I have no basis for assessing it in terms or outcomes, rebound issues, cost effectiveness, opportunity cost in terms of other uses for the money etc.

In terms of delivering the Food Vision 2030 ambition of global leadership within a decade, it looks like we are on our own. The Commission is pressing ahead on metrics, which is essential, and their forthcoming study of emissions trading (due December 2023) will generate a lot of debate, but probably nothing of substance will be in place much before 2030 that will help do what we need to do to hold onto premium customers in key export markets.

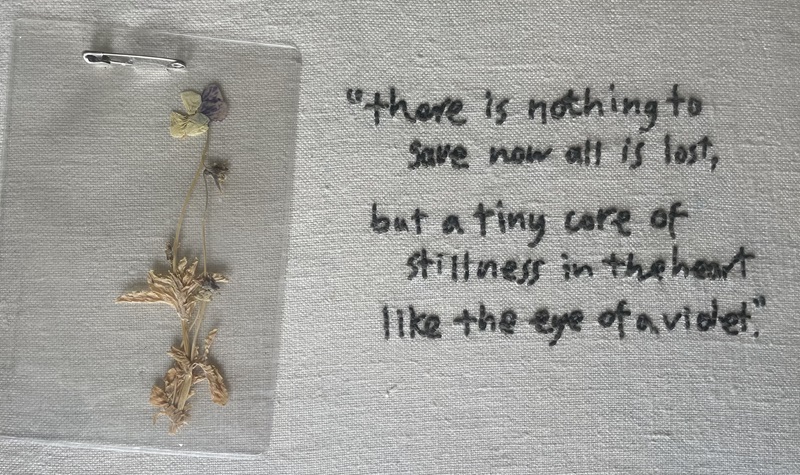

Finally, I take inspiration from the well-known final farewell of Seamus Heaney to his wife Marie, texted to her from his hospital trolley on his way into theatre in Blackrock Clinic, 15 minutes before he died: “Noli timere.” Do not be afraid.

Introduction

The final Blog 13 (Farmers) is devoted to farmers. This Blog 12 (New Instruments) is directed mainly at those in the Irish policy process. I apologise in advance to those many of you who already know much more than I do on this front; I just hope that pulling ideas and evidence together may also be of some marginal use to those many of you who are already way ahead of me on this curve.

In 2007, I with co-authors Susana Ferreira and Simon McDonnell published “The most popular tax in Europe? Lessons from the Irish plastic bags levy” Environ Resource Econ (2007) 38:1–11 [the unfair rules of the academy meant that Simon McDonnell (the student) did 90%+ of the work]. The-Most-Popular-Tax-in-Europe-Lessons-from-the-Irish-Plastic-Bags-Levy.pdf (researchgate.net).

Noel Dempsey was the Minister at the time, and he and his civil servants deserve a lot of credit for its success. Consultants who were asked to advise on the idea recommended to him that he apply the levy upstream, on the suppliers of bags, rather than downstream at consumer level. He rejected this advice: He wanted consumers to get a strong and immediate message: ‘Most plastic bags end up wasting precious resources and blighting our ecological and aesthetic environment. I want you to know that every time you shop, and your purchases are to be plastic-bagged, you will be directly incentivized to make a better choice.” Internationally, a few local jurisdictions had introduced levies, but Ireland was the first nation-state to do so. There are a few lessons here for all who are responsible for shaping Irish climate policy for farming:

- Courage is the first pre-requisite. Dempsey and his team went where no one had gone before.

- Small countries can lead when they have a mind to. I just had a look at ‘Google Scholar’ and see that our paper has been cited 520 times, many of those reading it no doubt wanting to know how it was done.

- Incentives that reward positive performance and penalize the opposite were the most important ingredient.

Framing is hugely important. Dempsey did not engage with the public to ask them whether they would agree with such a levy. He was familiar with Edmund Burke’s famous insight: “To tax and to please, no more than to love and be wise, is not given to men” and knew that they would have rejected it; its popularity came later. However, in engaging with the retail sector, he was open to discussions around the ‘how’. In New Zealand’s shaping of its climate policy, all sectors, including agriculture, were initially included in their national emissions trading scheme. When farmers vigorously objected, they were allowed to take time to propose to government an alternative scheme with the huge condition that the alternative(s) proposed be at least as climate-effective as inclusion in the trading scheme. The scheme they came up with – obligatory participation rather than ‘opt in’, and imposition of a levy on emissions – was accepted by the government. More details at: Blog 7 NZ.

- Some of the framing we observe around the Food Vision working group proposals is similarly wise.

The Three Challenges for the Irish Policy System and the Benefits of Meeting Them

There are three challenges: find ways that work to: reduce greenhouse gas emissions and remove carbon at scale; improve water quality in key catchments; conserve nature, with Natura 2000 sites prioritized. If you deliver these three outcomes, it will deliver five benefits:

- Discerning consumers (who are mainly richer than you and me, people with plenty of choices) in our premium export markets will stay loyal and their numbers are likely to expand. Sellers of Irish food in premium markets will be able to say to current and new consumers that, while they are paying more, they are buying nutritious food that tastes wonderful, which is produced by happy cows, while: lowering pressures on our precious climate commons - reducing greenhouse gas emissions and increasing carbon storage at scale - while increasing the competitiveness of our carbon footprint, improving water quality (nitrates↓), and restoring nature (Natura 2000↑). And these achievements are independently verified. This narrative will be very well received.

- At the next assessment, Irish derogation farmers will hold onto their 220 Kg/Ha derogation and the associated cost savings relative to having to operate within the 170 Kg limit. The latter is likely to be the consequence if nitrate concentrations in key catchments do not fall very significantly by the time of the next review.

- A step change in conservation of nature will see Irish farming moving towards compliance with the EU’s Nature Restoration Law

- Compliance with the ‘Green Claims Directive’ which is expected to be operational in 2026.

- The constant carping in the Irish media about Irish farmers and their doings will disappear like snow off a ditch, and the status of the farming profession will rise in esteem and attractiveness.

If you fail, the opposite happens: premium customers leak away, derogation farmers incur added costs, the Irish rural economy begins to wilt, a court challenge becomes likely, and the drum beat of criticism of farmers and farming intensifies with continuing and increasingly high psychic and other collateral damage borne mainly be farmers.

Mind Set

- This is a battle you must win: it will require change, which is always hard, and coordinated/integrated action across a number of departments which is always difficult.

- Remind those who care to listen, and those who don’t, that, as well as being in a battle for hearts minds and pockets, we are in a world where litigation is likely if a gap emerges between our climate claims and our performance. A lot of the claims I hear in public would not survive the forensic scrutiny they would receive in Justice Marilyn Huff’s court (on February 3, 2019, in her California court, she found in favour of Ornua (Kerrygold) when its grass-fed claim was challenged in a class action suit) or meet the requirements of the Greenwash Directive ; a loss in a court anywhere would do huge reputational damage and must be avoided.

- Bill Clinton won the US Presidency with one simple slogan: “It’s the economy stupid.” The equivalent in this battle is: “It’s the market stupid”. For nearly 5 years while living in New York city (2014-2018) I regularly paid about 60% more for a pound of Kerrygold butter than I would have paid for its main domestic rival (Land O Lakes). Premium markets for Irish food exist, and if they shrink, the future prosperity of Irish farming will atrophy also. If you don’t believe me do some comparison shopping on Walmart’s website - kerrygold butter - Walmart.com

- The EU is by far our biggest market - it is a huge net exporter of dairy products and is almost self-sufficient in beef. Climate policy in our top three export markets – in rank order EU, UK and US – is driving emissions reduction and carbon removal by their farmers at scale – the carbon footprints we will be competing with in the future in these markets will be much lower than they are at present, competition which will be intensified in the UK by tariff free competition from New Zealand and Australia.

Your policy mix needs to drive change in the three areas above, which means: generating action at scale in terms of emissions reduction and carbon removal; nitrates must decline sharply in key river catchments; conservation of nature in a growing number of flagship sites will capture positive international attention (Natura 2000 sites etc.). See; Figure 3 in: O’Rourke, Fiona, Claire Byrne, Gavin Smith, 2023: Land Use Evidence Review Phase 1 Synthesis Report Government of Ireland, p. 83

- It needs to deliver value for money. At this point, I believe that the crowd on Hill 16 at Dublin’s GAA games – most of whom see themselves as Ireland’s over-taxed taxpayers – will support serious new taxpayer investment in Irish farming, but only if they see it delivering the above results.

As I have done with the rest of the blogs, I first present key findings, adorned at times with some evidence, followed by a longer ‘Evidence’ Section in which I provide much more ballast in support of my conclusions. There is also a long Annex A which summarises the current and prospective roles for 11 government departments. Both sections are organized around the following headings: scope of opportunity; criteria for assessing performance’; instrument menu and assessment; whole of government.

Key findings

A. Scope of Opportunity

Climate: Farmers have two broad opportunities to reduce climate pressure. The first is reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the second is storing carbon (mainly afforestation) and reducing carbon losses (mainly raising the water table in peaty soils). There is still a question mark as to how different jurisdictions will count (or not) on-farm carbon removals and reducing carbon losses in their determination of carbon footprint, and this may evolve over time. Policy must deliver outcomes that perform across various metrics and in different jurisdictions.

Emissions’ Reduction: The sector is obliged by law to reduce emissions by 25% by 2030. Farmers and their food companies will need to achieve large reductions in order to deliver a carbon footprint that is competitive in future key export markets.

Carbon Removal: I apologise in advance for the too many pages I devote to this issue in the ‘Evidence’ section. My excuse is two-fold: I did forestry at UCD, and subsequently worked in this field in Germany, France, Switzerland and England, and saw how farmers and their communities embraced tree culture as integral to their business and social model. Secondly, it disturbs me greatly to listen to various voices make the case in Ireland that trees are the enemy of grass and therefore a threat rather than an opportunity. The new grant package (funded entirely by the Irish Exchequer, and recently approved by the European Commission) is very generous. It will be a tragedy and a huge own goal if the opportunity is not taken by many farmers to make carbon-removing trees part of their future business model. The losses of inaction would include foregoing: the resulting improvement in their carbon footprint due to carbon removal; tax free income in the range of €746 (Mixed high forest, mainly spruce) to €1,037 (mainly oak and beech) per hectare per annum for 20 years; future revenues from wood sales; opportunity for their successors to convert to agro-forestry.

Water Quality: The focus needs to be on reversing the performance that has resulted in reduction in the derogation from 250 Kg/ha to 220 Kg. There are 9 catchments of concern - Maigue Deel, Bandon, Slaney, Blackwater, Suir, Nore, Barrow, Slaney, and Boyne. Between 2013 and 2019, these catchments showed nitrate-increasing trends, and ~85% of the nitrogen came from agriculture, from chemical and organic fertilizers. Catchment-nitrogen-reductions-assessment---June-2021.pdf (epa.ie)

Nature Conservation: As is the case with water quality, we know where to look to find the biggest challenges and opportunities: ‘The Status of EU Protected Habitats and Species in Ireland, 2019’ Microsoft Word 01_AR1719_hab_1110_Sandbanks.docx (npws.ie) tells us about the full population of habitats and species that are recognized by the EU as being priorities. Only a subset of these is directly influenced by farming.. And there are habitats and species of concern that are not on this list which will need to be included.

Implications for the Irish Policy Process

There are two:

You need to fill Information gaps: What gets measured gets done. The main gaps at farm level are lack of data on carbon losses and removals and biodiversity at farm level. If farmers are to take these into full consideration, they need to know where they stand, and the outcomes they can influence. It would also be very helpful if you could promote the creation performance labelling of farms akin to the carbon efficiency ratings of buildings (A through G). A Working Group in Denmark has recently recommended this model for action by the Danish government See: https://fvm.dk/klimamaerke (use Google Translate to give you this in English or Irish)

- The EU’s Sustainability Reporting Standards (recently issued – see later) give you the tools to recognize the sustainability achievements of Irish food companies and to help them maximize the benefits thereof.

- You need to find and implement an effective mix of incentive and innovation policies: ‘effective’ means policies that will maximize the prospects of delivering the climate, water quality and nature conservation outcomes above and Food Vision 2030 ambitions to be a global leader.

B. Criteria

- Geography: The first step is to begin identifying where and what interventions are most likely to deliver the best value for money. An obvious place to start is the quality-challenged catchments, because this is where multiple benefits - reduced greenhouse gas emissions, and improved water quality – are to be found. The good news is that there are well-developed structures in place to both frame the challenges, and identify pathways for making progress at scale: How do we manage our catchments? - Catchments.ie - Catchments.ie and of course the list of EU Habitats and Species of Concern guide us to where the biggest payoff to efforts are likely to be in the biodiversity space. This framing is not evident in CAP 2023-2027. I share Brendan Dunford’s criticism: the imposition of a €7k payment ceiling on results-based payments, which is a de facto quota on ecosystem services. https://www.agriland.ie/farming-news/acres-transition-described-as-deja-vu-for-farmers-in-the-burren/ A key and understandable motivation in ACRES is to maximize the number of farmers taking up the scheme, and given the low incomes of many of the beneficiaries in the cattle and sheep sectors (Table 1) - there is a clear equity logic here, which is why new money and new ways of allocating it are needed to deliver ecological outcomes at scale.

Table 1. Average Family Farm Income and Farm Size by Farm System, 2016-2023, Ireland

| Farm System | Average Family Farm Income (FFI)(000s €) | Average Farm Size (Ha) | ||||||||

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023* | 2021 | 2016 | |

| Dairy | 54.0 | 90.2 | 63.3 | 69.2 | 79.0 | 98.7 | 148.0 | 105.0 | 64 | 56 |

| Cattle Rearing | 11.7 | 10.7 | 8.3 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 10.9 | 8.7 | 9.7 | 33 | 36 |

| Cattle Other | 15.0 | 16.3 | 15.1 | 14.1 | 15.5 | 17.2 | 16.9 | 17.3 | 36 | 37 |

| Sheep | 15.6 | 17.4 | 13.4 | 15.0 | 17.9 | 20.8 | 19.9 | 19.4 | 45 | 51 |

*Projected

Sources:

Income data for 2022 and 2023 (prospects): Outlook 2021 (teagasc.ie) pp. ii, iii

Income data 2016-2021 and Farm Size 2021: Dillon, Emma, Trevor Donnellan, Brian Moran and John Lennon, 2022. National Farm Survey 2021. 2022 - Teagasc National Farm Survey 2021 - Teagasc | Agriculture and Food Development Authority, p. xii

Farm Size 2016: Microsoft Word - NFS 2016 cover pages_long (teagasc.ie), p. 3

- Incentives Alignment: A second step is to map the existing incentives facing farmers and their food companies to take action or not in the most favourable geographies. For companies that sell to premium consumers e.g., dairy coops and their members that are benefitting from the ~60% premium in the US butter market, the incentives are aligned. However, there may be coops and companies who are selling mainly into commodity markets where their meat and/or milk is blended with product from many disparate sources and who have limited if any interest in premium markets.

- Value for money: I make the case above.

- Inclusivity: While it is true that you won’t deliver the outcomes at the scale and cost you need unless policy drives change in the most favourable geographies, it is essential that it also be framed to support and incentivise farmers who are outside these boundaries, and support needs to reflect the income realities of their situation.

- Innovation: Climate policy would have failed for: energy and industry in the absence of an innovation strategy that first developed renewables that were technical substitutes for fossil fuels, and then dramatically reduced their costs; transport until batteries were developed that were technical substitutes for diesel and petrol, and then ways were found to dramatically increase their range and reduce their costs. The EU has an Innovation Fund which continues to channel billions of Euros (funded by top slicing of auction revenues from EU ETS) to further support innovation in these sectors. There is no equivalent for farming. R&D is necessary but not sufficient to drive innovation.Denmark (population 5.8 million) led the world in development and commercialization of wind energy. The key characteristics that maximize the prospects of successful innovation are: crisis, good policies that are sustained, mission focus, learning by doing, relevant research and development, direct ‘outsider’ involvement, global reach, luck. The biggest challenge we face is that the biggest investments in innovation globally are happening where indoor containment farming dominates and advances are likely to be best suited to this sort of farming, which in time could deliver them carbon footprint competitive advantage. See Blog 11 Innovation.

Implications for the Irish Policy Process

- Small countries matter most globally when they innovate. The EU should have an innovation fund for farming equivalent to what is provided for the rest of the economy and Ireland should be an innovation leader generating new and better options for grass-fed farming.

- Get the incentives right, especially where the payoffs to effort are likely to be greatest.

- River catchments are emerging as an important geographic identity in Ireland, where progress especially on reducing climate pressure an improving water quality can be combined.

C. Policy Instruments

Milton Friedman observed that: “When crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.” In the case of climate policy for Irish farming, those ‘lying around’ and therefore in use, are subsidies (mainly CAP), regulation (mainly the Nitrates Directive), information (mainly Teagasc) innovation (mainly R&D), increased efficiency (mainly R&D and advisory), voluntary agreements (mainly bonus payments by coops for climate and environmental actions). Those not yet in use include tax/levy on emissions (to be applied in NZ); emissions trading (the potential for an EU-wide scheme specific to agriculture is being considered by European Commission); nine categories of tax expenditure two of which delivered significant commercial benefits to farming in 2021 (value in brackets) namely CAT - Farm Relief (€199.7 million) - and Reduced Rate on MOT (Green Diesel) (€522 Million); zoning/spatial (e.g., environment compliant concessions for ruminant farmers whose farms have very low carbon footprint); green purchasing (e.g., government only buys food from companies who have high ratings under the recently issued Sustainability Reporting Standards, 2023 European Commission ANNEX I Regulation for European Reporting Standards, 2023 - Search (bing.com) which requires of companies with more than 500 employees that (p. 72) “GHG emission reduction targets shall be disclosed for Scope 1, 2, and 3 GHG emissions, either separately or combined”).

Learning from Experience

At a meeting of the Food Vision Committee, a member asked (I am paraphrasing) ‘Who has successfully addressed the climate challenge in farming, and what can we learn from them’? It was amongst the most important interventions I heard, and it was never systematically addressed. The EU has benefitted hugely from such learnings in other climate policy areas: Its design and delivery of its greenhouse gas emissions trading scheme (EU ETS) to deliver emissions reduction at scale from the power sector and heavy industry benefitted hugely from the success of the US in the design and delivery of its acid rain (SO2) emissions trading scheme, which reduced emissions from the power sector by 40% faster and at much lower cost than alternative policies and its regulation of the carbon efficiency of light vehicles was informed hugely by the success of the US regulation of Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency (CAFÉ) Unfortunately, I was late in the day seeking out documented examples for farming from which we could learn, but I did find material on a few that are useful which I summarize below, and reference to others that I did not get to, but which could be a useful source[3].

The California Experience: Details are available at: Jimenez, Frank, 2021. Assessing California’s Climate Policies—Agriculture, Legislative Analyst’s Office, (LAO), California, Assessing California’s Climate Policies—Agriculture, December 22 pages

Beginning in 2015, it has had two grant aided programmes - the Dairy Digester Research and Development Program and the Alternative Manure Management Program. The criteria by which applications will be judged are based on points out of 100 allocated in the case of the Alternative Manure Program as follows:

Outcomes (50): Estimated greenhouse gas emissions reduction (35); Environmental co-benefits 10); Benefits to priority populations (10)

Quality of inputs (50): Project plan and long-term viability (25); budget and financials (15); project readiness (10). Details at: 2023 AMMP Request for Grant Applications. For those whose bids were successful, the Dairy Digester programme provided two financial benefits to farmers: on the supply side, they benefitted from subsidies, and on the demand side, they benefitted from (1) revenues generated from selling biomethane (or electricity generated from biogas) and (2) environmental credits under the state’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) Program and the federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) Program.

Emissions reductions achieved by 2022 were ~3.5 Million tons of CO2e, of which ~1/3 was a result of cow number reductions. There is not much to be learnt from what they fund, but there is a lot to know about how they do it, mainly: the inclusion of dairies and farmers in the invitations to bid; the fact that the process is designed to ‘discover’ where the best value for money is likely to be; the transparency of the process; and the fact that we can see the ex-ante estimates of outcomes and their ex post achievement.

The French Offset Programme (Label Bas Carbone): This was initiated in 2018, so there is 5 years of experience. It puts a lot of effort into ensuring additivity, creating a market (airlines have to buy offsets to cover emissions by domestic flights and the two coal power plants have to do likewise to cover their emissions) and documents outcomes (Forestry 843,000 tonnes of CO2e removed and Agriculture 734,000 tonnes of CO2e emissions reduced), and prices secured per tonne (€8-125). I will provide more details on request.

European Innovation Projects: Brendan Dunford (co-founder and former manager of the Burren Programme) observed that there were three parts to their success in delivering nature conservation at scale: information, incentives, and heart. He also noted that: “Farmers do not respond to being told what to do but instead, having learned about biodiversity, they respond to being told what the result should be. Farmers were also provided with clear information, were helped with paperwork and participated in a variety of community projects. The final element of the work was recognising the identity and heart of the farmers as critical”. Citizens’ Assembly, 2023. Report of the Citizens’ Assembly on Biodiversity Loss, March Report-on-Biodiversity-Loss_mid-res.pdf (citizensassembly.ie) p. 85

Learning from Farm-Foresters: a total 25,000 (mostly farmers) benefitted from planting grants since 1990. A detailed interrogation of a small sample of this population would yield fascinating and useful insights about how best to design and deliver the new programme. Find them and learn from them.

Learning from Doing: Many Irish farmers are getting on with reducing emissions and nitrate pollution of rivers, and conserving nature. We need to keep learning in real time about their successes and failures and adapt policy to reflect these learnings.

Implications for the Irish Policy process

- Exploring new combinations: There are a very large number of policy instruments available for use by the Irish policy process, many of them under the aegis of the Department of Finance. It would be a very useful exercise to interrogate each separately and in combination to explore what range of outcomes might be delivered. Examples on the tax expenditure side: adapt the Farm Relief (CAT) tax expenditure to favour farms with a carbon performance rating of B or above; remove the VAT exemption on chemical fertilizers, and recycle all the revenues accruing back to farmers proportionate to their reduction in the use of fertilizer [Sue Scott, then at ESRI recommended a version of this in 2004 (Fertiliser taxes - implementation issues | ESRI)]. The first-round effect (higher prices) would reduce use (stick) and this would be amplified by recycling the revenues to those who reduced chemical fertilizer use (carrot).

- A new subsidy programme designed along California lines – available to individuals and combinations of individuals, farmers and coops and companies - which has two strands – climate and water quality; nature conservation – and is designed to discover what applicants are willing to do at what cost, and support those whose combination of outcomes and means of achieving them are most promising and best value for money.

- Openness to the New. Examples: The EU is studying the creation of an emissions trading scheme for farming only; NZ will be reporting lessons from its emissions’ levy approach etc.; and the US is driving its Agriculture Innovation Mission for Climate (AIM for Climate) which since COP 26 has invested more than $8 billion USDA Highlights AIM for Climate Accomplishments, Announces 2023 Plans | USDA.

D. All of Government approach

The current Irish government identified 12 cabinet posts as members of its Cabinet Committee on the Environment and Climate Change. The departments represented in the Cabinet Committee are matched by the relevant Secretary Generals of these departments, who form the Climate Action Delivery Board. In the Annex of the Climate Action Plan 2021, details are provided of each of the 493 actions proposed, including department responsible for each. These are important steps. Below a few ideas, accepting that I am in ‘teaching grandmother to suck eggs’ territory here.

Building on this Progress

It is essential to prioritize – out of the 493 actions what are the 10-20 that are crucial to making progress and scale, and how can we maximize the prospects that these will be delivered on time?

In Annex A below, I identify 11 of these government departments, summarize their key roles and (if stated) their climate specific commitments, and then assess their roles include some suggestions for prioritization. I found it useful to group the 11 departments into three categories:

The Core (4): Taoiseach, Finance, Expenditure and Public Reform, Environment Climate and Communications

Direct Action (2): Agriculture, Food and Marine and Housing Local Government and Heritage – but of course DECC also has responsibility for direct action by the energy and transport sectors.

Support Action (5): Foreign Affairs, Rural and Community Development, Further and Higher Education Research and Innovation, Enterprise Trade and Employment, Tourism Culture Arts Gaeltacht Sports and Media.

Implications for the Irish Policy process

I read somewhere that the Climate Action Delivery Board (Sec Generals) has never met. This is encouraging. The opportunity costs of their time are huge and what issue would justify them all getting together? There is a strong case however for sub-groups meeting to address key barriers and opportunities. A few thoughts amplified by some suggested priorities in Table 2.

- I noticed in the Taoiseach’s ‘Statement of Strategy 2023-2025’ that a role of its Climate Unit is “unlocking barriers in our transition to a low-carbon, climate-resilient, resource efficient and environmentally sustainable economy and society”. It could be hugely useful if it engaged bilaterally with some of the members to identify one priority action they each could lead on that would relax one barrier that is inhibiting progress, and then find ways that work to do so.

Table 2 Supporting Climate Action by Irish Farmers – and all of government responsibility.

| Department | A Key Existing Priority | Future Priority | |

| CORE | Action | Thought Leadership | |

| Taoiseach | Whole of government effectiveness and unlocking barriers | Set up and manage two sub-groups of the Climate Action Delivery Board: (1) Core and (2) Direct Action | Small countries can make big difference |

| Finance | Carbon tax and its ring-fencing of ensuing revenues for climate action | Exploring new direct and tax expenditure instruments options that would drive climate/water quality/nature conservation at scale | Generate an evidence-based national conversation on options that will reduce emissions and store carbon at scale, and then make decisions. In the Climate Action Plan 24 draft I read: “CP/24/2 Consider a number of reforms to the taxation system under relevant indirect tax heads from an environmental perspective”.“CP/24/26 Consider further opportunities for issuing new Irish Sovereign Green Bonds, and monitor the allocation and impact of funds raised through existing Irish Sovereign Green Bonds” These are important ideas. |

| DEPR | Ensuring value for money, and using a shadow price for carbon applied in its economic appraisals of public policy | Upgrade IGEES and especially its ex-post assessment capacity and link it to the work of the ‘new Climate Science & Policy Analysis unit within the EPA’s Climate Change Programme’ proposed in the government’s CAP24. | Value for money matters. |

| DECC | Ensuring progress on sectoral targets | Celebrating achievement and innovation | Yes, we can. |

| DIRECT ACTION | |||

| DAFM | Emissions↓ Removals↑ Selected River quality↑ Selected Natura 2000↑ | Payment for performance | The commercial case for supporting the farming transition to high quality stewardship of climate water and nature is compelling. |

| Housing Local Government and Heritage | Selected River quality↑ Selected Natura 2000↑ | Prioritization of and investment in key opportunities for improvement at scale. Zoning for conservation is welcomed by most farmers | Geography matters. The quality of rivers and of natural habitats as a source of pride and distinction and economic and social advantage |

| KEY SUPPORT | |||

| Foreign Affairs (DFA) | Using Irish Aid to support farmers like Constance Okollet* | Key bridge between Irish farming and emerging technologies, policy and consumer sentiments in four key markets – EU, UK, US, China | Irish grass-fed farming can show the way |

| Rural and Community Development | Sustainable inclusive and empowered communities: Build local capacity in relation to climate change adaptation and mitigation | Celebrate communities and especially their farmers in whose catchments water quality is improving, climate pressure is falling and nature conservation is expanding | Find ways that work to bring community talents and energies into driving both adaptation and mitigation. |

| Further and Higher Education Research and Innovation: | Funding ‘Farm Zero C’ | An Innovation Strategy that maximizes the prospects of new and lower cost ways of reducing and storing carbon at scale in Irish grass-fed farming. | Ireland (pop 5.1 million) can do for global ruminant farming what Denmark (Pop 5.8 million) did for wind energy |

| Enterprise, Trade and Employment (DETE) | “Advance the green and digital transitions to ensure the competitiveness and sustainability of Irish based enterprise | Special tax and support arrangements for Irish food companies that deliver and sustain outstanding climate and environmental performance | Irish food internationally epitomizes the highest standards of climate water and nature stewardship. It is an ambassador for Ireland as a whole. |

| Tourism Culture Arts Gaeltacht Sports and Media | Mobilise emotion and sentiment to engender action [Fear (‘we are doomed unless…’) is not working] | Fight for nature like a hero** | |

* Constance Okollet is a small-scale farmer and community organizer: “In eastern Uganda, there are no seasons anymore. Agriculture is a gamble… This is outside our experience…” Climate change is already destroying the lives of those who have done nothing to cause it” quoted in: Robinson, Mary, 2018: Climate Justice – hope, resilience and the fight for a sustainable future, Bloomsbury.

** This is a riff from George Bernard Shaw: “This creature man, who in his own selfish affairs is a coward to the backbone, will fight for an idea like a hero.”

- If you agree that making parallel progress on climate water and nature is essential, and that river catchments and Natura 2000 sites are key geographies for doing so, then a sub-group of General Secs from DAFM, DECC and Housing Local Government and Heritage and the relevant agency heads could set strategic direction and TORS for a Working group to find ways that work to convert ambition into outcomes.

- In policy design and delivery, Finance (allocation direct funding or tax expenditure) and DEPR (value for money) have to be always in the room as have key agencies (Revenue Commissioners were crucial in successfully shaping the plastic bags levy). It would be great if we could act on Sue Scott’s proposal in 2004 to remove the VAT exemption in fertilizer and re-cycle the ensuing proceed to farmers proportionate to extent to which they reduce use. Better late than never.

- An outlier: We are not winning the battle for hearts and minds. Fear is not doing it. I suggest that Tourism Culture Arts Gaeltacht Sports and Media be asked to find a way that works better.

Evidence and Assessment

This addresses scope for action; criteria for assessing performance; policy instrument menu, institutional arrangements.

Scope for Action

There are two broad opportunities where dairy, beef and sheep farmers can address climate change: The first is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and the second is to remove carbon dioxide and reduce carbon losses. Both involve the use of land. Below, I first summarise the land available, and who owns it, and then turn to the first opportunity, emissions reduction. The Food Vision 2030 report recommended that separate groups be formed to address how to meet the 25% emissions reduction target. This is the first time that the potential was formally addressed with stakeholders. I summarize the measures that these groups recommended. I then address carbon removal, with the focus on forestry, both the existing estate, and increasing it by afforestation. Because the data are under review, I do not address the opportunities to reduce carbon losses.

Land Use

The total area available for land-based emissions’ reduction, carbon removal and reduction of carbon losses is 7.1 million hectares. Its distribution by land use and by ownership is shown in Tables 3 and 4: As regards ownership, it is striking how much land (13.8%) is classified by the authors as ‘unmapped’.

Table 3. Land Use by Category (% of Total) and Total Land Area (000s Ha), Ireland 2020

| Year | Grassland | Wetland & Peatland | Cropland | Forestry | Settlement | Other | Total Land Area (000s Ha) |

| 2020 | 59 | 17 | 10 | 11 | 2 | 0 | 7,112 |

| 1990-94 | 62 | 19 | 10 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 7,112 |

Source: Land Use - CSO - Central Statistics Office

Table 4. Private and Public Land Ownership, Ireland

| Land Use | % of total |

| Private | |

| Farmland (Not Commonage) | 67 |

| Farmland (Commonage) | 7.2 |

| Forestry | 3.4 |

| Total Farmland and Forestry | 77.60 |

| Total Private | 77.68 |

| Public | |

| Forestry | 5.7 |

| Local Government | 1.7 |

| Fuel and Energy | 0.7 |

| Central Government/Agency | 0.7 |

| Total Public | 8.47 |

| Unmapped | 13.8 |

| Total | 100 |

Source: Byrne, Claire, Thomás Murray 2023: Land Ownership Analysis, National Land Use Evidence Review Phase 1 Document 03, p. 6

The three largest categories – pasture, wetlands, and forestry – together account for 87% of Ireland’s land, and most of this is owned by farmers.

Scope-Emissions reduction

The Emissions baseline in 2019 for the 3 ruminant farming systems are shown below:

Table 5. The Baseline: Scope for Climate Action – Addressing Emissions from Ruminant farming Ireland 2019

| Category | Million Tons CO2e |

| Dairy | 8.2 |

| Beef | 7.4 |

| Sheep | 1.9 |

| Total Farming | +22.1* |

*Of which enteric methane is 13.6 million tons, 61.5% of total.

Sources: Total Farming -Table Blog 1 (Looking Back); Dairy and Beef – Table 1 Blog 10 (CAP 2023-2027)

The two most specific and important proposals to address reducing emissions from ruminant farming are the Food Vision reports produced by the stakeholder groups for dairy and beef:

Table 6. Direct Measures proposed in the Report of the Food Vision Dairy Group

| Direct Measures | Impact (Mt CO2 eq) | Cost |

| 1. Reduce chemical nitrogen use by 27-30% by end 2030 | 0.37 | 30% reduction in chemical nitrogen reduce profitability per hectare by 15%, in a scenario where cow numbers are held constant, and the reduced grass production was made up by purchased feed. But:increasing the adoption of Low-Emissions Slurry Spreading (LESS);improve Nitrogen Use Efficiency; encouraging Clover Adoption and Multi-Species swards (MSS) will reduce these costs |

| 2. Target a 100% replacement rate of CAN with Protected Urea by the end of 2025 | 0.33 | No additional cost. Protected Urea is cheaper than CAN on a cost per kg of Nitrogen basis |

| 3. Development of methane mitigating feed technologies | 0.43-1.00 | Initial manufacturer reports suggest €75 – 100 per cow per year |

| 4. Develop methane Mitigating Breeding Strategies | 0.30-0.4.00 | Genotyping strategy initial costs is estimated by ICBF at €19m/ per annum for the dairy herd with cumulative cost estimates at €152m for dairy sector to 2030 |

| Total 1-4 | 1.43-2.10 | |

| 5. Voluntary Exit/Reduction Scheme | 0.45 per 100,000 dairy cows reduced |

Source: Report of the Food Vision Dairy Group, October 25, 2022, p. 2-4. Shown as Table 12 in Blog 10 (CAP 2023-2027).

Table 7. Direct Impact measures Food Vision Beef Sector, 2022

| Measure | Emissions reduction | Cost |

| Million Tonnes CO2e | € Millions | |

| 1. Improve liveweight performance | 0.57-0.82 | 0 (No regrets) |

| 2. Reduce age of first calving of suckler beef cows | 0.05-0.12 | 0 (No Regrets) |

| 1. Develop methane-mitigating technologies | 0.15-0.30 | 11.3-29 million |

| 2. 90% replacement of CAN by protected urea | 0.20 | 0 (No regrets) |

| 3. Chemical U use ↓ by 27-30% by 2030 | 0.26 | To be determined |

| 4. > Organic beef prod to 180,000 hectares | 0.20 | €37 million provided in CAP 2023-2027. Net private costs to be determined |

| 5. Breeding strategies (carbon sub-index) and building efficiency traits | 0.10-0.30 | €80.9 million by 2030 |

| TOTAL | 1.53-2.18 | |

| 6. Voluntary Diversification Scheme | 0.6/100,000 suckler cows | €1,080/suckler cow for farms exiting |

| 7. Voluntary Extensification Scheme (< no suckler cows) | 0.6/100,000 suckler cows | €1,380/ suckler cow for farms reducing |

Source: Government of Ireland, 2022: Report of the Food Vision Beef and Sheep Group to mitigate Greenhouse Gas Emissions from the Beef Sector. Food Vision 2030. November 30. Also shown as Table 13 in Blog 10 (CAP 2023-2027).

Scope – Carbon Removal and reducing carbon losses.

The carbon removal issue arises on two fronts: the existing forestry stock, and the increase in this stock from afforestation.

The Existing Forestry Stock

Total Stock: In Table 8, I show the carbon removals (with negative sign) and CO2e emissions from forestry, wood harvest, crops, grass and wetland and the total net removals for Ireland, as estimated and projected by the European Environment Agency (this data will have been provided by the EPA).

It is striking how quickly emissions from forestry are expected to change from net CO2 removals of over 2 million tons in 2020 to net losses of over 2 million tonnes in 2025, increasing to projected carbon losses of over 4 million tonnes in 2035. These radical changes appear to be a product mainly of better estimates of CO2 losses[4] from trees planted on blanket bog. However, the sharp decline in planting in recent years, and the harvest of trees that, if left growing, would continue to remove carbon, are also likely to be relevant. The carbon embedded in some wood products that are a product of such harvesting is shown in ‘wood harvest’; such removals are expected to increase to 2025 and fall back to 2022 levels in 2030 and 2035.

State Forest Stock: In August 2022, Coillte published Forests for Climate - Report on Carbon Modelling of the Coillte Estate. This report details an assessment undertaken to determine the current Greenhouse Gas profile of Coillte’s existing managed forest estate (see especially section 4.1) and to identify and assess the GHG mitigation potential of silvicultural management options based on a number of assumptions.

Private Forest Stock: There are two main sources of private stock: the first is the existing small but important number of forests which were retained in private ownership when, until it was dissolved in the late 1990s, the Land Commission was buying up landlords’ estates with a view to transferring the ownership to farmers who could draw down loans from it for part of the price. The second is the small forests created by the over 25,000 landowners (most of whom are farmers) who have benefited from afforestation grants and annual (premium) payments, covering ~285,000 hectares. Because much of this planting took place in the west of Ireland - ~104,000 (36% of the total) were planted on Cork, Kerry, Clare, and Mayo[5]- a significant share of this was likely planted on blanket bog.

Adding to the Forest Stock

In its assessment of land suitable for afforestation, Teagasc concluded that: An area of 3.75 M hectares is deemed suitable for afforestation; Productive land represents 2.45 M hectares and marginal land represents 1.3 M hectares; An area of 178,000 ha currently classified as unimproved land may offer a significant potential to increase afforestation rates; A total of 450,000 ha (12% of the ‘suitable land’) are required to increase the area to 18% forest cover.[6] However, the Haughey et al (2023) report notes that: “This level of afforestation falls short of the rates compatible with net-zero targets by mid-century (based on the indicative scenarios developed in this report), which are between 20,000 and 35,000ha/yr– depending on whether or not CH4 (methane) is included in net-zero targets”.[7]

Table 8. Removals and Emissions Land Use and Land Use Change, 2020 to 2035, 000s Tonnes CO2e, Ireland

| Year | Forestry | Wood Harvest | Crops | Grass | Wetland | Total |

| 2020 | -2085 | -819 | -111 | 6895 | 2760 | 6926 |

| 2022 | 363 | -1609 | 5 | 7569 | 1665 | 8046 |

| 2025 | 2065 | -1954 | 14 | 7663 | 1637 | 9654 |

| 2030 | 2832 | -1606 | 97 | 7817 | 1677 | 11063 |

| 2035 | 4219 | -1665 | 167 | 7899 | 1677 | 12568 |

Source: European Environment Agency, 2022. GHG projections – 2022 – EEA_csv

From Row numbers beginning at 2356, and columns B, D and G.

Note: Emissions from ‘Settlements’ not shown, but included in ‘Total’

A tool is available that provides estimates of emissions removal (sequestration) by: species, their productivity (Yield Class) and the soil type (mineral, peaty mineral, eligible peaty soils) in which they would be planted - Forest Carbon Tool - Teagasc | Agriculture and Food Development Authority. I show a few examples in Table 9

Table 9 Estimated mean average annual sequestration (removal) rate, by selected species and soil type.

| Species (Yield Class) | Mean Sequestration Rate (Tonnes CO2/Ha/Year) by Soil Type | Remarks | ||

| Mineral | Peaty Mineral | Eligible Peaty Soils | ||

| Sitka Spruce (YC 24) | 8.32 | 6.54 | 4.76 | |

| Sitka Spruce (YC 12) | 2.48 | Estimates only available for peaty soils | ||

| Oak (YC 6) | 2.31 | Estimates only available for mineral soils | ||

Source: Forest Carbon Tool - Teagasc | Agriculture and Food Development Authority.

CHOOSE: Click HERE; Accept Assumptions; Approved Species; Category; Soil Type; Calculate

ALERT: The carbon tool was developed in 2015, before the latest research on carbon losses from blanket peat was available: as noted, the latter has changed the estimates of CO2 losses and so the estimates above for peaty mineral and eligible peaty soils are likely to change. Also, it does not include the categories listed in the menu proposed for support under CAP 2023-2027.

Although the numbers are expected to change for peaty soils, the table does highlight the large range of carbon removals by productivity and soil type.

A programme which increased the amount of the initial grant, and the amount and duration of the annual premium payments has recently been approved by the European Commission: which are likely to stimulate to increase the range and diversity of the planting. I show a few examples in Table 10. These were recently approved by the European Commission.

Table 10. Grants available for Afforestation, Ireland, 2023-2027

| Forest Type | Grant/Ha € | Premium/Ha € | Duration of premium (years) | |

| Farmers | Non-Farmers | |||

| Native Forests | 6744 | 1103 | 20 | 15 |

| Agroforestry | 8555 | 975 | 10 | 10 |

| Mixed High Forest (mainly Sitka Spruce, 20% broadleaves) | 3958 | 746 | 20 | 15 |

Source: Afforestation-Rates-for-the-Forestry-Programme-2023-2027.pdf (teagasc.ie)

The new planting grants are very generous, and with the licensing process improved, it is reasonable to expect a rise in planting rates. Since 2017, there have been guidelines in place to restrict planting on unsuitable sites.[8] These are due to be updated for the next forestry programme which is due to commence this year. As part of the development of the Forest Strategy 2023 to 2030, the Department is reassessing its policy as regards future afforestation on organic soils.

An important recommendation of the Citizens’ Assembly Report on Biodiversity loss is:

“As a matter of urgency areas and species of High Nature Value, including but not limited to the national network of Natura 2000 sites and protected species, should be protected from further degradation through the implementation and enforcement of existing legislation and directives.”[9]

O’Donoghue (2022) assesses the economics of afforestation by land type.[10] The key finding is that incomes from farming are such that, with the grants then applying, for many such farms, there is limited short-term commercial case to convert land now producing milk and meat to producing wood. However, he notes that Department of Public Expenditure and Reform uses a shadow price for carbon which it has used in its economic appraisals of public policy; these rise from €46 per tCO2e in 2022 to €100 in 2030 and to €265 in 2050. If farmers were rewarded per ton of CO2e removed at this rate: “About 50% of all farms would have a higher income from forestry than agriculture for Sitka Spruce and about 30% have a higher return for broadleaf; 11% of specialist dairy farms would have a higher return from forestry, while nearly 80% of cattle rearing farms and 70% of cattle finishing farms would have a higher return from forestry.”(see p. 5 of summary report). These calculations were published before the new grant rates were announced (see above) which will be wholly funded by the Irish Exchequer, and which will cost ~€1.3 billion up to 2030. Also, there is no discussion of the potential effects of carbon footprint, and how this could influence access to premium markets and their prices.

Assessment of Scope

- Farmers own most of the land (of which ~ 4 million hectares is grassland) and are therefore in pole position to play the key role in reducing emissions, removing carbon (mainly afforestation), and reducing losses (mainly raising the water table of carbon rich soils).

Reducing Greenhouse Gas Emissions

- The Food Vision reports identify the measures that could reduce emissions by ~25% by 2030 by the dairy and beef sectors, but they do not discuss the policy instruments that could be mobilized to deliver these measures. Discussion thereon is deferred until I address the relevant policy instruments (both current and potential) below.

Carbon Removal and Reducing Carbon Losses

The Existing Stock of Forests:

- Continue to improve the metrics of carbon removal and carbon losses in aggregate by Coillte (state) and at farm level (private).

- For those forests (mainly planted on blanket peat) that are losing carbon, identify the best practises to reduce these losses over time. For those that are removing carbon, find ways that work to continue to do so, while integrating the delivery of other commercial (mainly wood) and public (mainly biodiversity and water quality) services. We can see the beginnings of this work in: Forests for Climate - Report on Carbon Modelling of the Coillte Estate[11] and a sense of its complexity in Ken Byrne’s (University of Limerick) statement to The Oireachtas Committee on Environment and Climate Action, 22 November 2022 available here.

- A particular focus should be on learning from those 25,000 landowners who planted forests since 1990. They need to know the carbon removal/losses of their forests and they deserve to get help in either optimizing removal and/or reducing losses.

Afforestation

- At present, agriculture is a separate ‘pillar’ to land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) and so carbon removed by farmers will not be counted towards emissions’ targets for farming. However, removals by farmers (categorized as ‘Scope 3’) who are supplying a food processor are likely to counted in the computation of the food’s carbon footprint in some markets. [ Silver Fern is New Zealand's largest livestock processing and marketing company, owned in equal partnership by Silver Fern Farms Co-op Ltd, a cooperative of 16,000 New Zealand sheep, cattle and deer farmers and Shanghai Maling Aquarius Ltd. This company claims to produce “New Zealand’s first certified Grass-Fed end to end Net Carbon Zero red meat, where 100% of end-to-end emissions have been offset within the farms where the animals were raised… It purchases this carbon from farmers to account for the emissions associated with the meat produced within the program…We have labelling approval from the USDA on our Net Carbon Zero claims.”] https://silverfernfarms.com/us/en/our-range/net-carbon-zero-science.

- Farm owners have important advantages over others in terms of tree planting: they own the land, and don’t need to incur the capital costs of acquisition; they are in place, and this reduces the costs of managing the forest; the carbon removed will contribute to their net emissions’ status, and this will help them in some markets retain or achieve ‘premium’ status as regards product prices; they can produce commercial output, which complements other income streams, and can also deliver other public goods, including biodiversity.

- The more productive the soil, the greater the diversity of tree species that will thrive, and other things being equal, the greater the volume of carbon removed.

- But there are trade-offs: More productive land for trees is also usually more productive for grass; some species (mainly coniferous) deliver more carbon removal earlier than do others (mainly broadleaves), but the latter continue doing so for longer; diversity of species is valuable ecologically but can incur diseconomies of scale.

- Important trade-offs are posed by the need to address the imperative of the Citizens Assembly that ‘areas and species of High Nature Value, including but not limited to the national network of Natura 2000 sites and protected species, should be protected from further degradation through the implementation and enforcement of existing legislation and directives.’ Policies must be designed and implemented that support farmers in these jurisdictions to do so. The trees that such farmers are allowed to plant are likely to deliver high biodiversity benefits but provide relatively lower carbon removals in the medium term. The grants for both nature conservation and afforestation should be integrated, and reflect the income foregone from conventional farm practises. There is some recognition that farmers in such areas need more support; the cap on payments for such farmers is increased from €7,000 to €10,000 annually.[12] However, given the constraints such farmers are likely to face, the prospects of success would have been greatly enhanced if the payment levels were much higher, and (if justified ecologically) perhaps confined to a small number.

- Delays in securing licenses to plant have been a factor in the sharp fall in planting in recent years. One constraint has been the shortage of forest ecologists to assess the habitat and other environmental issues arising. This is being addressed by DAFM, which in 2021 recruited 27 ecologists, and there has been progress also in developing a list of (47) independent experts.[13]

- There will be competition from ‘outsiders’: Private investors are likely to decide to buy land and plant trees, and the new grant rates are likely to encourage this to happen at scale; non-profit groups, communities and local authorities are also likely to become more engaged, especially if farmers opt out. From a climate point of view, it does not matter who does the carbon removal.

- But it will matter for those farmers who chose not to engage and thereby forego the associated benefits, including especially the carbon removed, which in turn will reduce their carbon-competitiveness in some premium markets. Presumably this is part of the reason why the period for which the annual premium is payable is biased in favour of farmers (typically providing an additional 5 years of payment compared with non-farmers).

- There are economies of scope and scale: it could help if groups of farmers, perhaps members of a coop, decided to aim for a shared planting and carbon removal target, and mobilized together to secure it, and together claimed the aggregate removals of the shared effort.

- There are risks and uncertainties to manage. These include: diseases, such as the fungal pathogenHymenoscyphus fraxineus which has in recent years devastated the native ash[14]; forest fires, which in future are likely to increase in intensity and duration; future decisions in some markets not to allow carbon removals by farmers to be credited towards their carbon footprint.

Grassland and Wetlands: the net carbon losses from these two sources are large, together amounting to close to 10 million tonnes annually over the period, with some growth in emissions from grassland compensated by equivalent reduction in losses from wetland. However, research on the extent of these emissions is also ongoing, so these estimates may be revised. Because both the metrics and the choices to reduce emissions are still under review, I do not address this opportunity.

Criteria for Assessing Performance

Much of the text below is taken directly from Blog 9.

Evidence on what works from climate policy experience in the energy, transport, industry, and buildings tell us that the following criteria will be relevant to the shaping of climate policy for ruminant farming.

- Achieve Outcomes at Scale: the volume of greenhouse gas emissions reduced, and carbon dioxide removed; degraded rivers restored to ecological health; Natura 2000 sites restored.

- Deliver Value for Money (Cost-Effectiveness) – the cheaper it is to reduce emissions and improve rivers and nature, the more you can reduce for a given amount of expenditure. To the extent that they must pay for this themselves, this also matters hugely to those doing the abating, and to governments when they are sub-venting action and have to raise the revenues necessary to do so.

- Provide Fairness - this has at least three dimensions. Are those who are most responsible for the problem doing most to address it? Secondly, are those who have the most capacity to do so being asked to do most? Are the needs of the most vulnerable being addressed?

- Relax the Critical Constraint(s): The payoff to effort will be magnified if policy finds ways to remove the constraints that are most inhibiting effective action. The lack (apart from > efficiency) of low cost means of reducing enteric methane is a key constraint.

- Achieve Multiple Benefits: in addition to reducing emissions and storing carbon, climate policy can also deliver other benefits, such as: commercial returns in markets where carbon footprint per Kg of product is important; public goods produced by farming, including more nature conservation, reduced air pollution (ammonia) and water pollution (excess N and P).

- Participation required above a certain scale. Where participation is voluntary, those who opt in may lose their ambition and enthusiasm if/when they observe others opting not to engage.

C. Policy instruments

Economies of Scale and Scope

In the delivery of both climate (emissions reduction and carbon removal) and biodiversity (diversity of species supported) ambition there are economies of scale – which can reduce costs – and scope – which can widen and deepen the variety and quality of outcomes delivered. These very large benefits can better be delivered with a group of farmers – e.g., those in a dairy co-op who are members of a co-op, or those who are supplying meat to a company that aims to be globally competitive in terms of its carbon footprint. However, I accept that some farmers will prefer to act alone.

Using Subsidies to deliver Scale and Scope

Note: There is a wider discussion on subsidies and emissions trading below.

Groups of farmers, ideally in cooperation with a processor (co-op or company) and in a catchment, would be invited to bid for grant support. Inter alia, their tender would identify: the individual farmers who are party to the bid; their baselines (climate, water, biodiversity); the mix of abatement and carbon removal measures envisaged to be undertaken, implications for water quality, and their estimated capital and operating costs; how effort will be distributed across farms from most to least prosperous; organization (structure, skills, budget) that will deliver these outcomes; business plan that will maximize the benefits of the climate, biodiversity and other outcomes. For suitable short-listed candidates, funds will be made available to help prepare the bid and decisions on those to be funded will be made by independent assessors, based on the overall credibility of the bid, its ambition and cost effectiveness, fairness in terms of how effort is allocated and innovation.

Funding: The above approach has the following advantages over the subsidy approach being used in CAP 2023-2027 (details in Blog 10). It will help: ‘discover’ those who are willing to do most; integrate water quality and biodiversity into decision-making; deliver public goods outcomes that are value for money; and achieve scale in terms of outcomes both in terms of reducing carbon footprint and aggregate net emissions (reductions and removals)

Comparative Advantage: enable farmers to do what they do best – e.g., some will have an obvious comparative advantage at doing emissions reduction (both technical measures and changes in farm system) and others at removal, and still others will find that their niche is habitat conservation. A coop could create a framework for finding what worked best, and this could include an informal emissions trading scheme, where farmers of a certain scale could trade internally, where those who could reduce emissions at low cost could be compensated for doing so by those for whom costs were high, so that overall ambitions were delivered, at much lower aggregate costs than if each farm had to deliver the same reduction.

The Policy Instruments being applied to Climate Policy for Ruminant Farming at Present

Milton Friedman observed that: “When crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around.” The most important idea ‘lying around’ is a regulation - the Nitrates Directive. The other instruments that are already in use to address climate change in agriculture and land use are Information, innovation, subsidies and increased efficiency. Taking each of these in turn:

Regulation

A core aim of the Nitrates Directive (91/676/EEC), which has been in place since 1991, is ‘to protect water quality from pollution by agricultural sources and to promote the use of good farming practice.’ The crisis is the evidence (see above) that, since the removal of the milk quotas, it has failed to do so. All EU Member States are required to prepare National Nitrates Action Programmes (NAP) that outline the rules for the management and application of livestock manures and other fertilisers.[15]

Derogation

Ireland is one of four member states – the others are Belgium (Flanders), Denmark, and the Netherlands - who avail of it. Member states applying for a derogation (or a renewal of a derogation) ‘must make a presentation on the environmental situation, the need for the derogation and actions undertaken to ensure that the higher nitrogen limit is not and will not contribute to higher pollution.’[16] The directive sets a limit on organic (manure) deposits of N per hectare per year on grass land of 170 Kg per hectare, but if certain conditions are met, the limit can be increased. A key condition imposed in 2022 in Ireland is “All slurry applied on the farm must be by applied by Low Emission Slurry Spreading (LESS) equipment.”[17] The increase allowed for ‘derogation farmers’ is at present 250 Kg N per hectare, but it has been reduced to 220 Kg N for 2024: As we know, Ireland failed the essential ‘will not contribute to higher pollution’ test, with the inevitable outcome that the derogation has been reduced.

Extension of the Industrial Emissions Directive (The European Commission agreed this proposal April 5, 2022).

Inter alia, it aims to: “Cover additional intensive farming and industrial activities, ensuring that sectors with significant potential for high resource use or pollution also curb environmental damage at source by applying Best Available Techniques.”[18] A threshold of >150 cows is proposed as the determinant for inclusion.[19] Commission proposals are decided jointly the Council of Ministers (member states) and the European Parliament’ Agriculture Committee proposes the exclusion of all extensive farming, small-scale family farming, and organic farming from the scope of the IED. EU parliament agri committee rejects 'permits' for family farms (agriland.ie)

Assessment