Lessons from a decade of climate politics in Ireland

Friday, 17 January, 2025

With the publication of the draft Programme for Government this week by the incoming coalition of Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael, supported by Independents, Dr Cara Augustenborg (UCD School of Architecture, Planning and Environmental Policy) reflects on ten years of analysing and assessing Irish governments on their climate and environmental policies and performance.

Leinster House, Dublin (credit: (opens in a new window)Jean Hausen)

Government formation in Ireland tells many interesting stories, particularly when it comes to the evolution of our national approach to climate and environmental policy. In tracking the process from the publication of political party manifestos to the evolution and progression of Programmes for Government since Ireland’s (opens in a new window)2016 General Election, I have watched with great interest as politicians went from “zero closer to hero”, accepting and responding to the science of our actions and their impacts on this precious planet we call home.

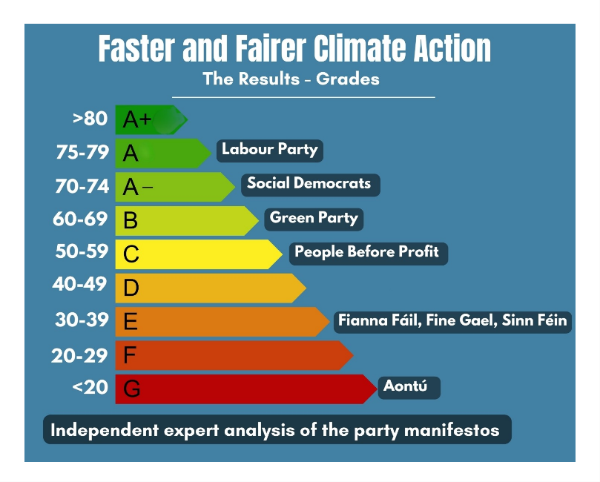

In 2016, only four political parties included dedicated climate or environment sections in their election manifestos. In the 2024 General Election, every political party had such a section and three of the nine parties went so far as to integrate climate action comprehensively across their entire manifestos. In less than a decade, our two main political parties (Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil) have transitioned from seeing the climate crisis as something to be “(opens in a new window)balanced with other competing policies” and demonstrating their resistance to wind energy to parties that are competing with each other on green credentials. In the (opens in a new window)2024 RTE Leaders Debate, Taoiseach Simon Harris pointed out twice that Fine Gael out-scored both Fianna Fail and Sinn Fein in (opens in a new window)Friends of the Earth’s manifesto analysis, though all three political parties received failing grades. After the launch of the 2025 Draft Programme of Government this week, (opens in a new window)Tánaiste Micheal Martin said this programme is “as ambitious” as the previous 2020 Programme for Government regarding “the need to address climate change and the challenges of biodiversity.” This seemed unlikely given the Green Party’s involvement in government in 2020 compared to their absence in 2025. However, a first analysis of the 2025 Draft Programme for Government indicates the Tánaiste may be right.

Leader of Fine Gael, Simon Harris TD, addresses the first sitting of the 34th Dáil as Micheal Martin TD, leader of Fianna Fáil, watches on, December 2024 (credit: (opens in a new window)Houses of the Oireachtas)

It is crucial to start by saying that, while the 2020 Programme for Government was widely lauded as the “(opens in a new window)strongest [on climate action] of any government we have ever seen”, it was far from perfect and (opens in a new window)criticised for its lack of concrete measures to reduce agricultural pollution and end the burning of coal and peat for electricity, among other things. However, with over 270 commitments related to climate and environment, there was enough content within the 2020 Programme for Government to allow civil society to hold a “flame to the feet” of government. Alongside my UCD Environmental Policy students, I had the pleasure of tracking progress on those 274 commitments over the last four years as part of (opens in a new window)Friends of the Earth’s Annual Report Card of Government. The importance of the commitments within a Programme for Government became crystal clear through that process. Each year, we spoke with government officials and public servants who took those commitments seriously, (opens in a new window)fully completing 60% of them and making significant progress on another 35% before the end of their tenure.

In an (opens in a new window)independent annual evaluation of the Government’s performance on those climate and environment commitments, academics (including myself) gave Government a C+ after their first year (2021); a C in their second; a C+ in their third; and a B- in their final year of government (2024). (opens in a new window)Our final assessment expressed relief that Ireland had finally “turned a corner away from our ‘climate laggard’ origins” with a 7% reduction in emissions in 2023. However, we also acknowledged that “this is just the start of a long and important journey for Irish society, and momentum will have to accelerate over successive governments to make Ireland a genuinely sustainable economy.” The assessment process demonstrated the importance of having strong commitments from the start of government formation.

Scorecard of political party manifesto commitments on climate action produced for 2024 general election commissioned by Friends of the Earth Ireland

Roll on to 2025 when we now have a new (opens in a new window)Draft Programme for Government (PfG) on the table this week. By volume, the Tánaiste’s claim that this PfG is “as ambitious” on climate and environment is true. Both the 2020 and 2025 PfGs have approximately the same number of environmental commitments, though the latest PfG has significantly more in energy and transport and far less on water and agriculture. Of course, quality matters more than quantity, and there are some (opens in a new window)commitments of concern in the latest PfG which may in fact damage the environment rather than protect it, most notably:

- A commitment to ensure that “all measures under the Nature Restoration Law will be completely voluntary for farmers”, defeating the purposes of a law.

- A commitment to “work with farmers and industry to secure Ireland’s nitrates derogation at EU level by implementing the Nitrates Derogation Renewal Plan in support of retention” with no mention of working with scientists or other relevant stakeholders to improve worrying decline in water quality as part of this commitment.

- A major disconnect between climate policy and aviation policy with several commitments including lifting the Dublin Airport passenger cap; establishing air connectivity between Dublin and Derry City airports; and developing air cargo infrastructure as part of those efforts, all of which could undo efforts to reduce emissions in other sectors.

These are issues civil society must be prepared to do battle on, along with the impact of data centres and imported Liquid Natural Gas on greenhouse gas emissions, which are not clearly addressed in the 2025 Draft PfG although they are crucial to meeting climate targets. However, if my personal experience of monitoring government commitments holds true, the contents of the 2025 Draft PfG are enough to stay on the path of transition, particularly in the energy and transport sectors, though a sustainable future for agriculture and nature will be much harder to grasp.

Clear, measurable over-arching commitments will be useful to anyone concerned about climate change, including the new Government’s commitment to a 2040 emissions target and their recommitment to the 51% emission reduction target by 2030 set forth in legislation, along with a promise for a Whole-of-Government strategy to integrate the UN Sustainable Development Goals. In the energy sector, there are specific targets, including 9GW of onshore wind, 8GW solar and at least 5GW of offshore wind by 2030, along with a commitment to develop and accelerate the roll-out of new electricity interconnectors, all of which can be used to demand rapid deployment of renewable energy.

The road ahead will not be without challenges, but if the evolution of Ireland’s political landscape over the past decade teaches us anything, it is that change is possible.

Finally, the transport sector, with by far the most environmental commitments (68) in the PfG, is rich with measurable plans, including continued development of greenways and cycle routes; expanded School Transport Services; increased funding for the protection and renewal of the rail network; and a promise to ensure Local Authorities allocate space for EV chargers in town plans and new commercial car parks. While this is not the “system change” or “modal shift” of our dreams, it is a seismic change from the approach to national transport policy pre-2020, which was almost entirely dominated by roads and cars.

Former Green Party leader Eamon Ryan speaking in Dáil Eireann, 9 April 2024 (credit: (opens in a new window)Houses of the Oireachtas)

In my view, this may be the biggest legacy Minister Eamon Ryan leaves Ireland as he steps out of politics this month. As the first Minister for Transport who insisted on a 2:1 funding ratio for public/active transport versus roads, he deserves enormous credit for creating the financial redistribution we needed to realise that sitting in traffic was not the idyllic life we wanted. It has been said that Minister Ryan did the same for wind power when he was Minister for Energy from 2007-2011, and Ireland’s current 40% of electricity from renewable sources is a testament to his efforts and vision over a decade ago.

While the political parties in this new Government may not have the same kind of visionary environmentalists among their ranks, it is clear from their evolution in party manifestos and Programmes for Government that they have come a long way in a short time. Like everyone, politicians need more education to fully understand how extensive our environmental impacts are and how devastating their consequences can be if left unabated, but the Irish are fast learners and we have all come a long way in our understanding of the environment in a short time. The road ahead will not be without challenges, but if the evolution of Ireland’s political landscape over the past decade teaches us anything, it is that change is possible. With resolve, education, and accountability, we can still build a future that respects and preserves our home.

About the author

(opens in a new window)Dr Cara Augustenborg is an Assistant Professor in Environmental Policy at University College Dublin and a member of UCD’s Earth Institute. She is also a member of Ireland’s Climate Change Advisory Council and President Michael D. Higgins’ Council of State. Her research focuses on the social accountability of environmental policies. In that context, she is currently the Principal Investigator on EPA-funded research projects examining the (opens in a new window)administrative burdens of climate action plans and (opens in a new window)using worldviews to inspire and scale climate action.

Further Reading

- Cara’s 2016 General Election manifesto analysis is here: (opens in a new window)2016 General Election

- The Friends of the Earth Ireland 2024 Report Card of Government is here: (opens in a new window)Our final assessment

- UCD Earth Institute and Friends of the Earth Ireland’s 2024 General Election manifesto analysis is here: 2024 General Election

- Cara’s more detailed assessment of the 2025 Draft Programme for Government commitments is here: (opens in a new window)2025 PfG