The following article was written by Jenny Darmody and can be found on the Silicon Republic website here.

UCD School of Medicine's Dr Carol Aherne talks about the role cell regeneration plays in the human intestine.

UCD School of Medicine's Dr Carol Aherne talks about the role cell regeneration plays in the human intestine.

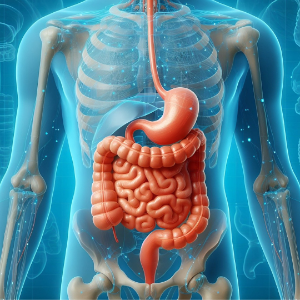

Regeneration is an important element of the human body. Skin cells replace themselves every few weeks. We get fresh liver cells about once every 300 days. The cells in our colon, for instance, are replaced every three to five days, while the complete skeletal regeneration can take a full 10 years.

It can be refreshing to think of yourself as a whole new you every 10-15 years but from a more practical, scientific standpoint, it could lead to game-changing innovation.

Dr Carol Aherne is an Assistant Professor at the University College Dublin (UCD) School of Medicine and a fellow at the UCD Conway Institute.

Her work focuses the intestinal lining, which is often damaged in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), allowing potentially harmful agents to cross into their body.

“This is thought to be one of the triggers for this lifelong disease. We study this lining in the lab to measure how it regenerates. One of the ways we do this is to watch how cells that are damaged move towards each other by looking down a microscope,” she told SiliconRepublic.com.

“From a practical standpoint, the overall research goal of my lab is to restore normal function of the intestine as a barrier. In diseases such as IBD, the intestine loses its ability to exclude particles from the outside world, which includes food particles and bacteria. To study this, we are measuring the ability of the lining of the intestine to grow and regenerate a strong barrier.”

In 2017, figures suggested there were nearly 7m people worldwide suffering from IBD. According to Crohn’s and Colitis Ireland, there are at least 40,000 patients in Ireland.

The disease has no cure and it can be a debilitating condition. According to Aherne, up to 50pc of patients fail current therapies after about two years.

“Therefore, identification of new therapeutic avenues, which we are working on in the lab, has the possibility to directly affect up to 3.5m IBD patients and a broader effect on society through increased engagement of individuals with daily life,” she said.

“This research has more far-reaching applications, in that damage to the intestinal barrier is suggested to contribute to many other diseases – for example, coeliac disease, diabetes and arthritis. If we can understand how to heal this barrier then our research could be applied beyond IBD.”

The importance of engagement

While the practical research is important, the science communication around it is also vital. Aherne said raising awareness of IBD is a critical point to early diagnosis and better treatment, especially as the disease becomes more prevalent.

“At present, there is a racial disparity in the context of disease severity, with African Americans being demonstrated to being more likely to be admitted to hospital than white Americans. So, by increasing awareness of the existence and prevalence of such a disease through engaging with racially diverse communities, we hope that we could make an impact on long-term outcomes.”

She added that collaborating with and listening to many diverse voices is important to learn from each other. “This is the only way we can ensure that the research we are doing has real-world relevance. To close the loop, we need to continue the conversations within the community on the progress of our research so that it can be seen how research can make a real-world difference,” she said.

And while the need for greater engagement seems like an obvious element, the barrier that can come with complex concepts is important to overcome.

“It is incredibly important that researchers are available to engage in a non-technical way, so that the possible impacts of their research in a real-world setting can be better understood,” said Aherne.

“I am encouraged to see that support for scientists to engage with the public is increasing, facilitated by great initiatives such as ‘Cut from the Same Cloth’, the ENGAGE series in UCD College of Science and Soapbox Science Dublin.”

While challenges no doubt exist, Aherne is encouraged for the future as she sees STEM engagement growing. “I hope this leads to at least 50pc more direct monetary investment by the Government at university level and investment in Research Ireland to bring us into line with other EU nations,” she said.

“Globally, I expect that interdisciplinary research will grow and I hope for more investment in basic research across all disciplines as knowledge of the fundamentals is essential to develop novel technologies and approaches.”