Opinion: Microbes might be gatekeepers of the planet’s greatest greenhouse gas reserves

Posted 12 November, 2020

Mikhail Varentsov / shutterstock

Massive greenhouse gas reserves, frozen deep under the seabed, are alarmingly now starting to thaw. That’s according to an international team of scientists whose preliminary findings were recently reported in the (opens in a new window)Guardian.

These deposits, technically called methane “gas hydrates”, are often described as “fiery ice” due to the parlour trick of burning atop a Bunsen burner what appears to be ice.

The research is not yet peer-reviewed and has been controversial, with some climate scientists saying the Guardian article makes (opens in a new window)unsupported claims. We agree that findings should be peer-reviewed before they are reported. But as experts in these exact methane hydrates, we’re more sympathetic than the climate scientists towards the idea that this a serious possibility that we need to start worrying about. So although it is controversial, let’s suppose for a moment that these latest findings are real and that methane frozen below the seabed really is being released. What does this mean?

Methane is not as common as carbon dioxide, but it also contains carbon and is a potent greenhouse gas. Many people have heard of methane being (opens in a new window)stored in Arctic permafrost, but few realise that there are also massive and (opens in a new window)much larger deposits of the gas locked beneath the seabed.

Although seabed greenhouse gas thawing has been foreseen – and feared – for some time, it was only suspected to become a serious problem by the (opens in a new window)middle of this century. If it now seems to be melting much earlier, its a signal that human indifference to the environment, and release of fossil fuel carbon, is now being effectively amplified by the disintegration of our own planet’s geological balance.

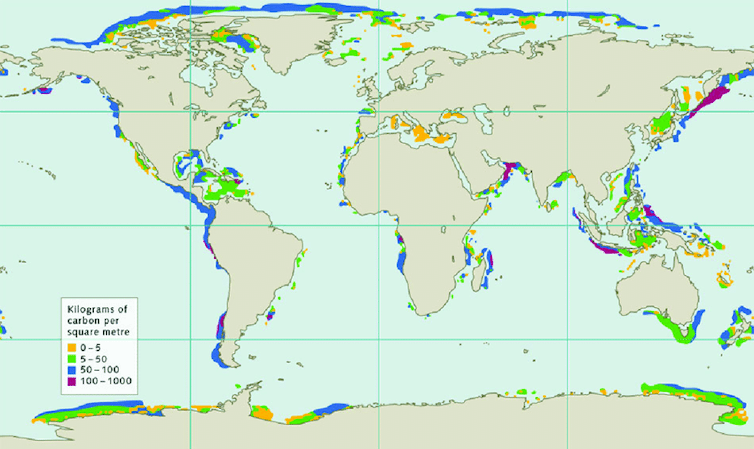

To put this into perspective, there is perhaps 20 times more carbon (opens in a new window)stored in these natural underground reserves than in the entire biomass of Earth combined – that is, (opens in a new window)all plants, animals and microbes. Clearly, there is at least the potential for greenhouse gas to be released from these deposits on a significant scale.

Methane entrapped in their icy jail cells of hydrates underground ought to stay there for (opens in a new window)millions of years, accumulating over the aeons. If these deposits are now rapidly thawing, we might think that basic physical parameters such as temperature and pressure are the only things that control their formation and destabilisation. If this was the case, then the problem could be easily understood, and even possibly mitigated through human intervention. However, it increasingly seems that other less predictable factors are also relevant.

Estimated methane hydrate occurrences in the world. (opens in a new window)World Ocean Review (data: Wallmann et al)

One unexpected influence is the Earth’s (opens in a new window)fluctuating magnetic field which, as we discovered in a (opens in a new window)study published last year can potentially destabilise the methane deposits. There’s even the possibility that this same effect could eventually lead to mass extinction: global gas-hydrate destruction may have caused the great (opens in a new window)end-Permian extinction event which wiped out 90% of species on Earth some 250 million years ago.

Microbes may be stabilising these methane deposits

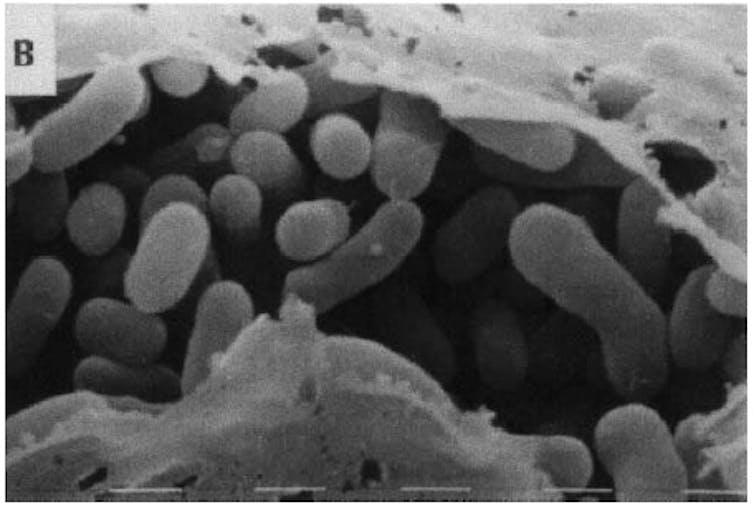

Another overlooked factor is the role of microbial life. Microbes have been with us for more than 3 billion years and are found just about everywhere on our planet, including deep beneath the seabed, in places we might otherwise think living things could not survive – let alone thrive. It seems perfectly natural then that these same microbes interact with stored hydrate reserves, perhaps even using the high-energy methane to flourish.

A kind of Methylobacterium, similar to the bacteria that lives off underground methane. (opens in a new window)Microbe wiki / Anesti et al

What if these microbes also stabilise their “food source”? Our research teams have recently shown that marine methane-using bacteria can easily (opens in a new window)produce simple proteins or “bio-molecules” that do just that. Furthermore, in (opens in a new window)laboratory experiments and computer simulations we demonstrated the accelerated formation of gas hydrates by such bio-molecules so that we can now conclude that microbes will indeed coordinate these reserves in the real-world conditions found under our seas and oceans.

The story becomes even more intriguing. We next studied the effect of both magnetic field changes and bio-molecules on the (opens in a new window)rates of methane-hydrate formation. These two factors appear to complement each other, so that microbes growing on hydrates in the presence of the Earth’s relatively weak, but changing, magnetic field could have adapted and evolved – no doubt over geological timescales – to control adeptly the massive methane-hydrate deposits that are found below the seabed and in the permafrost.

In other words: yes, microbes really may be the gatekeepers of this aspect of the Earth’s climate stability. If, and clearly it is still a big “if”, we have upset this delicate geo-microbial balancing act through global warming, then we won’t just be playing with fiery ice, we may ultimately see a world with temperature rises not seen since before the dinosaurs roamed the planet.

By (opens in a new window)Chris Allen, Professor of Cross-Disciplinary Microbiology, (opens in a new window)Queen's University Belfast and (opens in a new window)Niall English, Professor, School of Chemical and Bioprocess Engineering, (opens in a new window)University College Dublin

This article is republished from (opens in a new window)The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the (opens in a new window)original article.

![]()