Opinion: 2022 wasn’t the year of Cleopatra – so why was she the most viewed page on Wikipedia?

At the end of every year, I gather statistics on the most viewed Wikipedia articles of the year. This helps me, a computational social scientist, understand what topics captured the most attention and gives me a chance to reflect on the major public events of the year. I try to use data to determine how the public (and more specifically here, English-language Wikipedia readers) will collectively remember the past year.

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic, US presidential election, and Kobe Bryant’s death were among the most memorable events. According to Wikipedia readers, 2021 will be remembered for Netflix’s Squid Game, the men’s European Football Championship and the death of Prince Philip.

But in 2022, (opens in a new window)the list is topped by a somewhat unexpected name – Cleopatra.

Most articles at the top of the list are related to major world events, including the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the death of the Queen and the men’s football World Cup. Elon Musk and Johnny Depp also made the list. In addition to perennial favourites such as the Bible and YouTube, there are a couple of surprises that were probably influenced by external factors like media and popular culture.

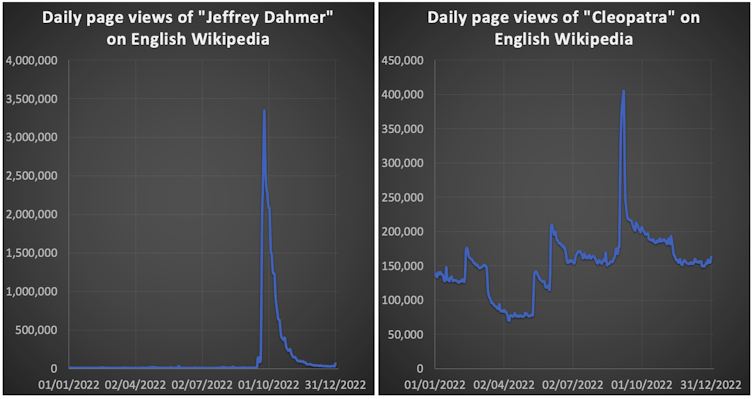

For example, the article about Jeffrey Dahmer, the notorious US serial killer who died in 1994, had more than 54 million views, coming in at number two. While aggregate page view statistics alone may not provide a complete understanding of why Wikipedia users were interested in certain topics, changes in view statistics over time can provide clues.

In the case of Dahmer, an increase in page traffic corresponds with the release of the Netflix series (opens in a new window)Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story on September 21. This suggests that the series may have prompted readers to learn more about Dahmer from Wikipedia.

However, the massive interest in the article about Cleopatra remains a mystery. While there were some news stories about (opens in a new window)a remake of the classic movie and (opens in a new window)a Superbowl commercial featuring Cleopatra, these do not fully explain the significant number of views. The day-to-day viewership statistics of the Cleopatra article also do not point to any specific event as the cause.

It also doesn’t show the typical rapid decay pattern of public attention. My colleagues and I have found (opens in a new window)in our past work that online attention usually has a short half-life of five to eight days, similar to what we see in the case of the Dahmer page.

Hey Google, tell me about Cleopatra

Trying to find the reason for the sudden spike in views of the Cleopatra article, I turned to the internet for answers. Soon, someone on Twitter (opens in a new window)provided a clue: the Google Assistant app, which uses voice recognition to allow users to interact with their phones through conversation, may be responsible.

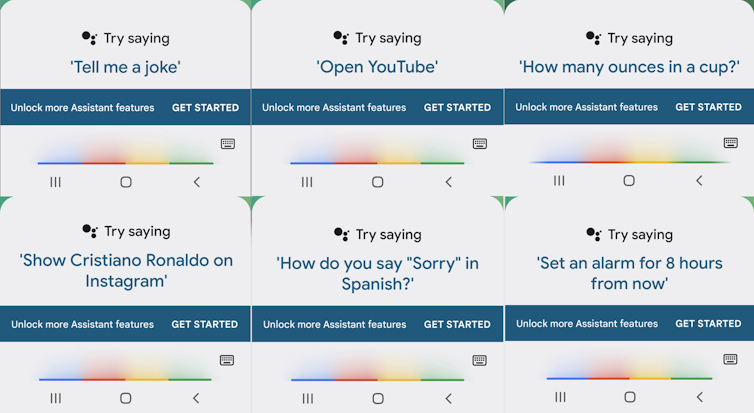

Launched in 2016, the app is now built into at least 1 billion devices and has (opens in a new window)more than 500 million monthly users. When you install the app and start using it, it provides examples of the types of requests you can make.

These include commands for your phone’s operating system, such as “Open YouTube,” or requests to initiate a web search, such as “How many ounces in a cup?” The app can also perform a combination of actions, such as “Show Cristiano Ronaldo on Instagram,” which would open the Instagram app and bring up Ronaldo’s profile.

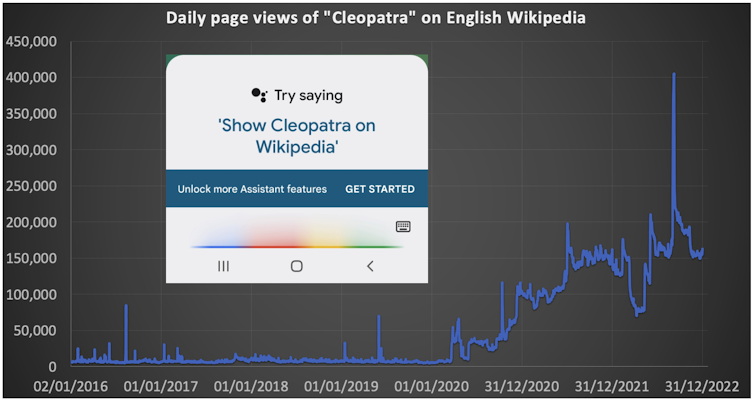

One of the prompts the app provides to demonstrate its capabilities is “Try saying: Show Cleopatra on Wikipedia”. Sure enough, in 2022, approximately more than 50 million people followed this prompt. Before Google Assistant (opens in a new window)became widespread in 2020, the annual views on Cleopatra were around 2.5 million.

Designing collective attention

The article’s popularity was probably greatly influenced by a prompt provided by the Google Assistant app, a seemingly arbitrary decision made by Google UX designers.

This is more than just an interesting coincidence. Researchers in the fields of social data science and web analytics often use statistics such as Google search volumes and Wikipedia page views to study attention and popularity dynamics. In addition to (opens in a new window)predicting the success of movies at the box office I used such data to (opens in a new window)study electoral popularity as well.

While these rather new data sources can be useful and exciting, and great proxies for monitoring human behaviour online, they can lead to misleading analysis. In 2013, Google researchers tried – (opens in a new window)and failed – to predict the severity of the flu season by analysing user search data.

It’s important for researchers in computational social science to also consider qualitative methods and in-depth case studies to understand the story behind the data.

More importantly, the Cleopatra example highlights the impact that seemingly small decisions by designers can have on directing collective attention to certain topics and issues, sometimes with more serious consequences. Google (opens in a new window)has been criticised for ranking search results in a way that prioritises its own products.

My previous research has shown how links on Wikipedia can (opens in a new window)drive significant traffic to certain articles, and how promoting certain petitions on the front page of a petitioning website can significantly (opens in a new window)alter the distribution of signatures and therefore chances of receiving widespread attention for certain political causes.

This phenomenon shows how a small change or design decision can have large-scale effects when it reaches millions of users through digital technology. In this case, no harm was done and maybe we learned a bit more about Cleopatra and her relationship with Julius Caesar. But the significant power that high-tech and media companies have in shaping and influencing public attention should not be overlooked.

By (opens in a new window)Taha Yasseri, Associate Professor, UCD School of Sociology; Geary Fellow, Geary Institute for Public Policy, (opens in a new window)University College Dublin

This article is republished from (opens in a new window)The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the (opens in a new window)original article.

To contact the UCD news team, email: (opens in a new window)newsdesk@ucd.ie![]()