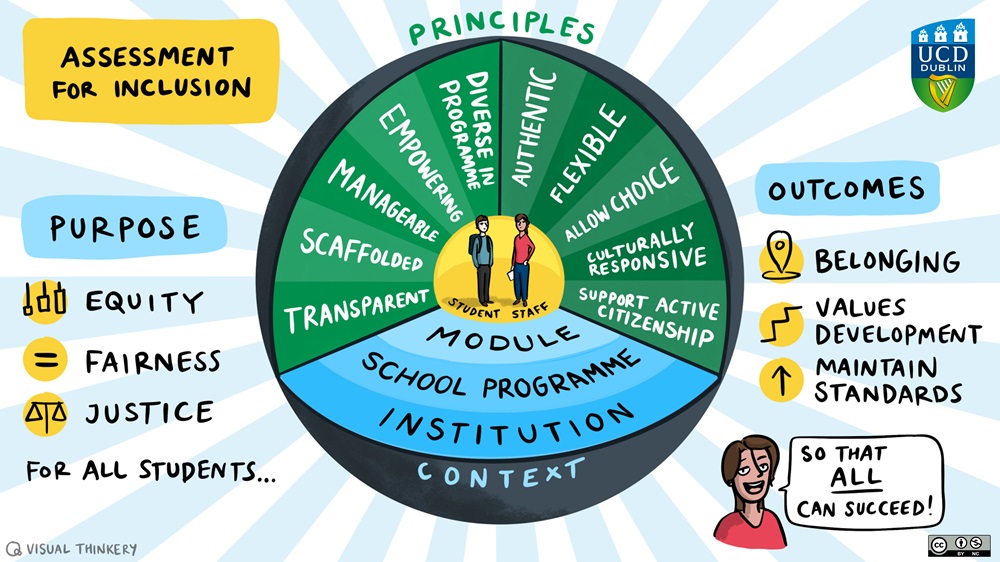

UCD Assessment for Inclusion Framework

The UCD Assessment for Inclusion (AfI) Framework is designed for staff who teach, in partnership with their students, to:

- Think about the meaning of ‘inclusion’, ‘equity, ‘fairness’ and ‘justice’ in the context of assessment (assessment literacy)

- Explore the purposes and benefits of adopting an Assessment for Inclusion approach

- Consider the practical use of the Assessment for Inclusion design principles

- Reflect on your professional values, identity and emotions in relation to Assessment for Inclusion

- Support dialogue between key stakeholders, in particular between students, staff and the wider institution

- Enhance your understanding of the processes for change related to Assessment for Inclusion practices and policies at module and programme levels

The resources on this page are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

The resources on this page are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

| On this page: | What is Assessment for Inclusion? | Why adopt Assessment for Inclusion? | Implementation Actions |

| About the Project | References |

What is Assessment for Inclusion?

In today's diverse higher education landscape, traditional assessment methods do not always meet students’ needs. Assessment for Inclusion seeks to create equitable assessment and feedback practices, enabling all students to effectively demonstrate their learning.

In today's diverse higher education landscape, traditional assessment methods do not always meet students’ needs. Assessment for Inclusion seeks to create equitable assessment and feedback practices, enabling all students to effectively demonstrate their learning.

The term ‘Assessment for Inclusion’ aligns with current literature and recognises that inclusion is at the heart of good assessment and feedback design and practice.

In line with UCD’s commitment to inclusion and Widening Participation (see the UCD EDI Strategy and Action Plan) Assessment for Inclusion seeks to support all students.

According to Morris et al. (2019), "inclusive assessment processes provide for all students whilst also meeting the needs of [a] specific group" (p. 437).

Consider reflecting on these questions:

- Do some of your students face situations or circumstances that disadvantage them in their assessments or feedback? Examples may include students who are parents, working, travelling long distances, part-time or international students.

- Do your current assessment and feedback methods give advantages to some students over others?

According to Hockings (2010), inclusive assessment is about creating fair and effective methods that enable all students to demonstrate their knowledge and skills to their full potential. Evans (2022) adds that this approach aims to create equitable access, enable participation and value student diversity. Inclusion is best integrated into assessment design from the outset. Recognising that no single approach can accommodate all students, the design principles may be used by faculty to guide assessment design decisions based on their specific context and needs.

[Assessment for Inclusion] captures the spirit and intention that a diverse range of students and their strengths and capabilities should be accounted for, when designing assessment of and for learning, towards the aim of accounting for and promoting diversity in society.

Tai et al. 2022, p. 485

Assessment for Inclusion isn't about making assessments easier or less robust, or letting students avoid assessment tasks that are fundamental to disciplinary knowledge. It's about enhancing practices to provide more opportunities for students to develop their knowledge and skills in a supportive and challenging environment (Kneale and Collings, 2015; Bain, K., 2023).

This includes using effective formative assessment strategies including feedback and feedforward, along with supporting students to learn how to evaluate the quality of their work. It is important for all students to be able to identify the strengths and weaknesses of their work and to develop skills to improve its quality. Inclusive approaches to assessment and feedback acknowledge student anxieties, and provide constructive support to help them demonstrate their learning (Winstone and Nash, 2016).

Why adopt Assessment for Inclusion?

Assessment for Inclusion approaches are underpinned by a commitment to equity, fairness and justice for all students. UCD is committed to creating an inclusive environment that celebrates diversity and ensures fair treatment for all, irrespective of gender, age, race, disability, ethnic background, religion, sexual orientation, civil status, family status, or affiliation with the travelling community (UCD EDI Strategy and Action Plan).

Fairness can mean different things to different people and is often described as interactional, procedural, or distributive (Vander Schee & Birrittella, 2021; Ling et al., 2020). Equity, sometimes used interchangeably with fairness, may emphasise using different approaches to assessment and feedback, rather than treating everyone the same.

Using the design principles, and reflecting on what is appropriate for the institution, school/programme and module context, this approach can:

- Build students’ sense of belonging in higher education

- Maintain academic standards and support assessment literacy

- Help develop personal and professional values

- Foster social inclusion and social justice

- Empower all students to succeed

What is ‘Student Success’?

This means different things to different students. In a recent Irish study, students identified various examples of success, ordered by frequency (O’Farrell, National Forum, 2019):

- Developing skills for employability

- Achieving good grades

- Completing their degree and graduating

- Deepening learning and understanding

- Doing their best and achieving personal potential

- Socialising and making friends

Implementation Actions

These actions are designed to help you (either individually or as a programme team) get started. You can follow them in any order, selecting what's most suitable and important based on your context and needs.

Action 1: Cultivating Self-Awareness

People are at the heart of Assessment for Inclusion.

It is about putting human beings at the centre of assessment and feedback, and aims to empower students to draw connections between their learning and their own diverse backgrounds, interests, experiences and future aspirations. It is an approach that recognises and responds to the increasing complexities of students’ lives and responsibilities.

Assessment for Inclusion approaches often involve meaningful or ‘authentic’ assessment related to ‘real-world’ situations, problems or scenarios. It can help to build collaboration and foster relationships between peers and students and faculty. It scaffolds and empowers students to take ownership of their learning, and supports them to imagine and develop their own distinctive contributions to the world as professionals and active citizens.

For faculty, Assessment for Inclusion approaches may mean interrogating assumptions or ideas about the purposes of assessment and feedback. It may involve thinking deeply about what we wish to achieve through assessment, and reflecting on opportunities to make the self more centrally integrated into assessment and feedback practices.

Start by developing your own self-awareness and that of your students about factors that impact inclusion in assessment and feedback (Henning et al., 2022). Use the following reflective questions to get you started. You are not limited to these questions and can choose which of these questions are most suitable to your context.

- How do your personal and professional values, as related to issues of inclusion and equity, shape your approach to assessment?

- Reflect on your own assessment experiences. Which suited you, or did not suit you, and how did you feel about them?

- What values are important for you (staff or students) to develop as part of the assessment and feedback processes?

- Should assessments be equitable even if that means different students do different assessments? Is that fair?

- Is inclusion only for specific groups of students or for all?

- What values are important for you and your students to have or develop through assessment and feedback?

- How does the assessment support student growth, development, and learning?

- How can students actively engage in the assessment process to support their own development?

- How does the assessment support students’ relationships with others, their community, and their discipline? How does it help them understand and engage with the world around them?

- What assessment or feedback issues or approaches are preventing students from succeeding?

- What does student success mean to you?

- Do you feel frustrated with current assessment and/or feedback practices?

- Are assessment practices stressful for you or your students?

- Do you feel anger or upset about some of the practices or policies in assessment?

- Does your assessment allow students to draw on prior learning and diverse cultural and global perspectives?

- What is your understanding of the knowledge of terminology, skills and attitudes around inclusive assessment and feedback?

- What is the purpose of your approach to assessment? Are you familiar with the key components of good assessment design?

Action 2: The Assessment for Inclusion Design Principles: Considering where to start

To improve your practice and policies, consider exploring whether your assessment and feedback approaches align with the Assessment for Inclusion Design Principles listed below.

These principles serve as guiding statements, bridging the gap between theoretical literature and the practical wisdom that informs everyday assessment literacy (Kremmel & Harding, 2020; Xu & Brown, 2016). They are based on literature, workshops, and research interviews with UCD staff, students and AfI international experts.

Feel free to review the design principles, but remember that not every assessment approach or context needs to address all of them. The emphasis on these principles may vary depending on factors such as context, discipline, time, and student groups.

Design principles

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should articulate a clear purpose, be in accessible formats, have clear documentation and clear criteria.

Assessment

By ensuring clarity and openness, educators can promote equitable opportunities for all students. Assessments must articulate their purpose explicitly. Students should understand why they are being assessed, how the assessment aligns with learning objectives, and its relevance. Clear communication of purpose reduces anxiety and empowers learners. McArthur & Huxham (2013) discuss the role of feedback as dialogue and share a helpful series of “moments” for embedding feedback throughout the learning experience.

Assessment guidelines, rubrics, and instructions should be transparent and in accessible formats which consider Universal Design Principles.

Students need to know what is expected of them, how to prepare, and how their work will be evaluated. Transparent documentation minimises ambiguity and supports student success.

Feedback

Assessment criteria should be explicit and well-defined. Analytic rubrics are a great way to ensure expectations are explicit. Students should understand how their work will be assessed, what constitutes excellence, and how grades will be assigned. Clear criteria empower students to meet expectations.

Key article

McArthur, J., & Huxham, M. (2013). Feedback unbound: From master to usher. In Reconceptualising Feedback in Higher Education (1st ed., pp. 92–102). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/

Other Links and Resources

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should be sequenced, continuous, and integrated to support student learning.

Assessment

Scaffolding assessment is specifically aimed at supporting students to learn, practice and improve their performance through engagement with feedback. In addition to enhancing student learning, it is also used to support academic integrity. Scaffolding of assessment refers to a range of mechanisms used to support students to successfully complete an assessment task. In addition to providing students with clear assessment criteria and rubrics, the use of formative assessment is key to scaffolding and monitoring learning, enabling students to improve their performance before submitting their work for graded evaluation. Scaffolded assessment is sequenced, continuous and integrated to support learning.

Feedback

While summative assessment is used to demonstrate achievement and is assigned a grade, formative assessment is typically a low-stakes or ‘no-stakes’ opportunity to effectively engage in a practice run or exercise and receive feed-forward.

Key article

Nicol, D., Thomson, A., & Breslin, C. (2014). Rethinking feedback practices in higher education: A peer review perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 39(1), 102-122 https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.795518

Other Links and Resources

- Jessica Kalra - Encouraging Academic Integrity Through Intentional Assessment Design: Scaffolded Assessments

- Stanford Teaching Commons - Formative Assessment and Feedback

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Feedback Strategies to Enhance Learning

- UCD Teaching & Learning - How to Give Constructive and Actionable Peer Feedback: Students to Students

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Self Assessment Tool

- University of Melbourne - Design nested or staged assessment

- University of Melbourne - Scaffolding Assessments: How and Why

- University of Melbourne - Peer Review

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should consider the assessment load for staff and students, be well paced, allow space for learning, be an appropriate weighting, be of equitable effort to similar assessments.

Assessment

Striking a balance between assessment volume and student capacity is essential. The volume of assessments significantly impacts students’ cognitive load. Overburdening learners with excessive assignments can hinder their ability to engage deeply with course content. The spacing of assessments matters. A crowded assessment calendar can lead to stress and hinder performance. Providing adequate temporal gaps allows students to reflect, revise, and recover. Moreover, considering mental space—students’ cognitive capacity—is crucial. Assessments should be spaced thoughtfully to prevent cognitive overload.

Assigning fair weight to different assessments ensures that no single task disproportionately impacts a student’s overall grade. Equitable weighting acknowledges varied strengths and preferences. Recognize that effort isn’t uniform. Some students face additional challenges due to disabilities, family responsibilities, or work commitments.

Feedback

Action specific feedback should be targeted and clear. Avoid vague feedback. Be clear about what the student did well or needs to improve. Give feedback as soon as possible, timely feedback is especially important when assessments build upon each other.

Key Article

O'Neill, G. M. (2019). Why don’t we want to reduce assessment? All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 11(2). https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/415

Other Resources and Links

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should give voice to students, support students in co-designing assessment, encourage them to judge their own work.

Assessment

Empowering students in their assessment and feedback allows them to have some control and ownership of the process. This may mean enabling students to share feedback on their ongoing experience. However, going a step further involves involving students in the design of assessments, empowering them to co-design their assessment (often referred to as Students as Partners.) For instance, students may be involved in the co-design of a rubric at the start of the module which will be used to assess their work (Morton et al, 2021). This may also mean giving students some choice in the approaches used. Another example is supporting students in the co-creation of the essay titles and marking criteria (Deeley & Bovill, 2017).

Feedback

Similarly, encouraging students to become more engaged in their own feedback by judging their own work (evaluative judgement) empowers them in this process (see our new SaP guide on ‘Enhancing the Student Role in Mastering Feedback’). For example, giving students choice in the feedback methods used (audio or written) and supporting them to request specific feedback that they would like. The use self and peer review is one key approach being used internationally (Concina, 2022)

Key Article

Shukla, A., & Arora, V. (2023). A holistic approach to student empowerment and assessment of its impact on educational outcomes through psychological ownership. Studies in Higher Education, 48(8), 1315–1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2197005)

Other Links and Resources

- National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning Assessment OF/FOR/AS Learning: Students as Partners in Assessment

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Empowering Students Through Assessment: Snapshot of Student Voice

Concina, E. (2022). The relationship between self- and peer assessment in higher education: A systematic review. Trends in Higher Education 1, (1), 41-55. https://doi.org/10.3390/higheredu1010004

Deeley, S. J. & Bovill, C. (2017) Staff student partnership in assessment: Enhancing assessment literacy through democratic practices. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 42(3), pp. 463-477. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1126551

Morton, J. K., Northcote, M., Kilgour, P., & Jackson, W. A. (2021). Sharing the construction of assessment rubrics with students: A Model for collaborative rubric construction. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 18(4).

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should support different assessment and feedback methods across stages/levels in a programme.

Assessment

Using diverse methods of assessment within a module and across a programme of study provides students with different ways to demonstrate their learning, knowledge and skills.

When considering how you might diversify your assessment:

- Reflect on the level of familiarity the students may have with the new approach. Have they experienced this approach before? Ensure that students are supported throughout the module to become more familiar with this approach.

- If introducing a new approach, you may need to remove an older approach so that the students are not overloaded.

- Using diverse assessment methods can support a more engaging learning experience, and allows for the effective assessment of a wider range of skills and knowledge.

Feedback

Using a range of (formative and summative) feedback approaches may be used across a module or programme. Feedback may be written, audio recorded, verbal, group or individual, or generated by lecturers, peers or self.

Key article

O’Neill, G & Padden, L. (2021): Diversifying assessment methods: Barriers, benefits and enablers. Innovations in Education and Teaching International. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2021.1880462

Other Links and Resources

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Key Assessment Types

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Programme Assessment and Feedback Case Studies

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Programme Assessment and Feedback Strategies

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Programme Mapping and Alignment

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Some Initial Ideas for Programme Assessment and Feedback

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should be relevant to the learner, collaborative, personalised, and linked to the identities of learners.

Assessment

Assessment that is more relevant, engaging, collaborative, personalised and linked with the identity of the learners is often described as ‘authentic assessment’, and by its nature is more inclusive. Authentic assessment involves students performing tasks that demonstrate their ability to apply specific knowledge or skills to ‘real-world’ situations (National Forum, 2017; Bosco and Ferns, 2014; Villarroel et al., 2018). Authentic assessment is linked to higher levels of student engagement and motivation.

The extent to which an assessment is authentic varies. Work-based assessment is considered to be highly authentic because students perform and are evaluated in real professional settings. Other forms of authentic assessment typically involve tasks that enable students to apply their knowledge and skills as if in a real-world situation. More recent thinking about authentic assessment includes its links with the student’s identity and how they can contribute to society as a whole (McArthur, 2022; Tai et al, 2017).

With the rise of the use of GenAI, there has been re-emergence of the use of authentic assessment, with one such example being the use of ‘Interactive Orals’ (Griffith University). Examples from different disciplines include: Product development (entrepreneurship); Business plan; showcase for industry (business); Product design project (engineering); Musical performance (music).

There are a number of key features of authentic assessment, notably:

- the transfer or application of knowledge and skills to a situation or problem

- the development and evaluation of professional skills and competence

- learning is demonstrated through a performance or product

- engages students in complex learning and metacognition

- may involve collaboration

Feedback

Authentic feedback shares traits with authentic assessment, emphasising more personalised and meaningful feedback for students. While rubrics may help to identify general areas for improvement, individual comments that highlight specific examples from student work are more authentic. Audio feedback can support this by directly addressing students and can feel more personal.

Key Article

Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S., Bruna, D., Bruna, C., & Herrera-Seda, C. (2018). Authentic assessment: Creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(5), 840-854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396

Other Links and Resources

Bosco, A., & Ferns, S. (2014). Embedding of authentic assessment in work-integrated learning curriculum, 15(4) 281-290,.http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11937/14964.

McArthur, J. (2022). Rethinking authentic assessment: Work, well-being and society. Higher Education,85(1), 85–101.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-022-00822-y

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Panadero E.. (2017). Developing evaluative judgement: Enabling students to make decisions about the quality of work. Higher Education,76 (3), 467–81.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0220-3

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should, where possible, support flexible deadlines and different approaches.

Assessment

Flexible assessment overlaps with the idea of empowerment and choice of assessment as it aims to provide some flexibility on the assessment and feedback approaches, in particular flexible deadlines and, where possible, flexibility in assessment weighting. This has been emphasised by Wanner et al (2021): students valued the opportunity of making a choice about their assignments, in particular, choosing their own dates for submission and the weightings for their assignments (p. 12).

Supporting students to have a window of opportunity to submit an assignment (for example within a week as opposed to one specific time), allows students to manage potential bunching of assessment deadlines and to manage their own workload. As with any degree of flexibility in assessment options, it is important to:

- Facilitate open and honest conversation with your students on the value of different options.

- Support students to make an informed choice

- Ensure your learning outcomes support that level of flexibility

- Be aligned with institutional policy and regulations regarding weightings/timings

More recently, there has been an increased emphasis in developing opportunities for flexibility in the weighting of assessment (STHLE.) Didicher (2016) describes two approaches to this as the ‘Bento and Buffet’ approach. However institutional practices which require a predefined assessment weighting, as is the current practice in UCD, may limit these approaches.

Feedback

To incorporate flexibility in feedback (as noted by STLHE) two deadlines could be provided: an earlier one with a grade, a rubric, and descriptive feedback, and a later one with just a grade and a rubric. Another example of flexibility in feedback is allowing students to choose between audio, video, or written feedback.

Key article

Wanner, T., Palmer, E. & Palmer, D (2021) Flexible assessment and student empowerment: advantages and disadvantages – research from an Australian university. Teaching in Higher Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1989578

Other Links and Resources

- STHLE - Use Flexible Assessment to Engage and Motivate Learners

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Empowering Students Through Assessment: Snapshot of the Student Voice

Didicher, N. (2016). Bento and buffet: Two approaches to flexible summative assessment. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 9, 167. https://doi.org/10.22329/celt.v9i0.4435

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should, where possible, allow choice within a module of assessment methods and feedback approaches, and support choice of topic.

Assessment

One approach to diversifying assessment is to enable students to have some choice in assessment. This allows students to play to their strengths, and can be realised through choice of assessment topics, methods, timing, questions and so on. One very valuable approach is to allow students to choose between two or more assessment methods within a module. Two or more assessment methods capable of assessing the same module learning outcomes empowers students to take responsibility for their learning. Embedding flexibility with choice of assessment can be particularly beneficial where there are diverse learning needs in a module including (but not limited to) students with disabilities, students with different prior learning, international students, mature students, and others.

Offering choice of assessment presents an inclusive alternative to traditional approaches, such as the provision of ‘special arrangements’ intended only for certain groups of students. An assessment strategy that integrates flexibility and choice in its design supports a more equitable and inclusive approach to learning that is available to all students. When considering the use of choice of assessment methods:

- Ensure that the choices given to the students are equitable, for example in student effort, feedback approaches, etc.

- The use of an Equity Template can help to achieve this.

- Prepare students to make an informed choice.

- Consider the advantages and disadvantages.

Feedback

As noted in the concept of flexible feedback, it is important to offer students a choice between audio, video or written feedback. Additionally, it is beneficial to ask students what specific aspects they would like to receive feedback on.

Key article

O’Neill, G (2023) Student choice of assessment methods: How can this approach become more mainstream and equitable? In R. Ajjaw., J. Tai, D. Boud, T. Jorre de St Jorre (Eds) Assessment for inclusion in higher education: Promoting equity and social justice in assessment. Routledge.

Other Links and Resources

- UCD Teaching & Learning - A Practitioner’s Guide to Choice of Assessment Methods Within a Module

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Key Assessment Types

- UCD Teaching & Learning - Student Negotiated or Choice of Assessment

Garside, J., Nhemachena, J. Z. Z., Williams, J., & Topping, A. (2009). Repositioning assessment: Giving students the ‘choice’ of assessment methods. Nurse Education in Practice, 9(2), 141-148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2008.09.003

Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., & Umarova, A. (2021). How do students experience inclusive assessment? A critical review of contemporary literature. International Journal of Inclusive Education. 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.2011441

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should be responsive to students from different cultural backgrounds.

Assessment

Culturally-responsive assessment supports students to make connections between their learning and diverse cultural backgrounds, experiences, perspectives and global contexts, enabling them to play to their strengths and interests as well as enriching disciplinary knowledge. This might include using assessments that encourage students to consider a topic from a range of cultural or global perspectives or take problem- or enquiry-based approaches to assessment that are based on authentic assessment contexts i.e., real world contexts or problems that impact global society at social, economic or environmental levels. Make assessment sufficiently open for students to research and draw on examples from their own and different contexts.

Feedback

Use clear language in feedback.

Key article

Bale, R., & Pazio Rossiter, M. (2023). The role of cultural and linguistic factors in shaping feedback practices: The perspectives of international higher education teaching staff. Journal of further and Higher Education, 47(6), 810-821. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2023.2188179

Other Links and Resources

- Australian Government (Leask & Carroll) - Learning and Teaching Across Cultures Good Practice Principles and Quick Guides

- Higher Education Academy - Strategic Enhancement Programme: Internationalising the curriculum toolkit

- Society for Research into Higher Education (Rossiter) - Feedback [hi]stories Exploring the role of linguistics and culture in feedback

Design Principle

Assessment and feedback approaches should, where possible, develop ideas and actions to support others in society.

Assessment

Assessment for inclusion goes beyond evaluating academic knowledge; it cultivates active citizenship. Inclusive assessments can mirror real-world challenges. By framing assessments around authentic problems—such as environmental issues, social justice, or community needs—students engage in meaningful problem-solving. This connection to real-life issues ignites their sense of agency and purpose. When students tackle real-life problems, they see the purpose behind assessments. It’s not just about earning a grade; it’s about making a difference. This mindset shift fosters active citizenship. Students become agents of change, applying their learning to create positive impact beyond the classroom. By embedding real-life issues, we empower students to connect their learning to meaningful action, nurturing active, informed citizens.

Feedback

Peer-to-peer feedback is a collaborative learning strategy where students review and provide constructive feedback on each other’s work. It encourages a deeper understanding of the subject matter as students not only learn from their own work but also from the work of their peers. This process fosters a sense of responsibility and critical thinking as students are required to articulate their thoughts in a clear and constructive manner and promotes a culture of openness and continuous learning, as students are exposed to feedback and different perspectives.

Key article

McArthur, J. (2016). Assessment for social justice: The role of assessment in achieving social justice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(7), 967-981. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1053429

Other Links and Resources

Action 3: Operationalise processes for change

While we can individually change our practices, changes to assessment and feedback have a knock on effect when key stakeholders (e.g. groups of faculty, staff, students) work together in a more systematic way. Therefore, UCD Teaching & Learning are suggesting that you bring stakeholders together to discuss and agree to changes at the stage level, or across related modules. This does not preclude you and others from working on your own modules. However, there should always be oversight and wider conversations around how these changes link in with other modules in your programme.

The context for Assessment for Inclusion

Assessment and feedback design and implementation are strongly impacted by the context. The context can be local (module, programme), and is usually strongly impacted by the discipline, and more widely at national and societal levels (micro, macro and meso levels). In addition, there are multiple stakeholders involved in each level. In the Irish context, assessment of learning means to supports students to achieve standards; whereas assessment for learning is engage with feedback on their learning and in addition, the national definition have separated out assessment as learning as it emphasis how students develop their skills to judge their own work (National Forum, 2017: O’Neill, McEvoy & Maguire, 2020).

UCD Teaching & Learning has developed a series of supports for implementing Assessment for Inclusion which suggests a three phase approach to bringing stakeholders together for a workshop/discussion on this topic. Feel free to download and adapt these workshop resources to fit your specific needs.

Phase 1: Pre-workshop

In this phase you should gather stakeholders and actively involve school/programme teams in understanding and identifying the specific needs of their teaching context. It is important to include students in the process. It may be helpful to complete the Assessment for Inclusion Survey for Schools/Programmes to determine the focus of the workshop and discussion.

Phase 2: Workshop

Set aside time for the stakeholders to meet and discuss in a workshop format. This could be facilitated entirely online or in-person (if facilitating in hybrid format, carefully consider how groups will work across the formats). You may wish to dedicate a half or full day to the discussion as it takes time to talk through the challenges. We have created a template to scaffold the workshop along with a worksheet for participants to record their thoughts through the workshop. This worksheet can be facilitated digitally or printed. It’s helpful to encourage participants to be detailed in their responses as this will help with post-workshop discussion and analysis.

Phase 3: Post-Workshop

Set aside time to discuss follow-up actions and any additional advice for implementing plans for change. Set realistic goals and timelines. You may wish to review and analyse worksheet responses and report back to the group at large with insights and recommendations.

Programme Level Actions

The workshop approach mentioned above can be a useful start in considering initial Assessment for Inclusion changes at module or stage level.

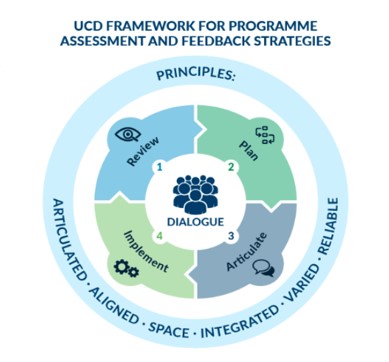

However, if you are a Programme Director, Dean, Head of School, Head of T&L in the School, you may wish to consider how to implement some of these design principles and changes to a whole programme or School. The institutionally approved ‘UCD Framework for Programme Assessment and Feedback Strategies’, along with its accompanying set of web and case study resources (see UCD Framework for Assessment and Feedback Strategies), can guide you through a much more significant change to assessment and feedback at programme level, i.e. to review, plan, articulate, and implement change. At the centre, it emphasises the importance of programme team dialogue in the change process.

The ‘UCD Framework for Programme Assessment and Feedback Strategies’, in association with the Assessment for Inclusion design principles, can be used to assist you through a significant change process at programme level.

About the Project

The UCD Assessment for Inclusion Framework is an action research project undertaken by members of UCD Teaching & Learning. The project is directed by Dr. Sheena Hyland and includes Dr. Geraldine O Neill & Leigh Graves Wolf. David Jennings and UCD Students as Partners in Teaching and Learning also contributed to the development of the project. The framework is the result of interviews with UCD students and staff and external experts, workshops and iterative cycles of research which resulted in the current presentation of the framework. The research team worked with Bryan Mathers (Visual Thinkery) to visualise the framework and key insights from the data which you see represented through this website. The project benefited from SATLE Funding (Strategic Alignment of Teaching and Learning Enhancement), administered by the HEA and National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning.

Research outputs

- Hyland, S., O’Neill, G, Wolf, L.G. (2024, June 20-21). The development of an ‘assessment for inclusion’ framework to support understanding, explore values and enhance practice. Assessment in Higher Education Conference. Manchester, UK

Poster: https://bit.ly/AfI-AHE2024 - O’Neill, G.M., Hyland, S., & Wolf, L.G (2024, April 17).UCD Assessment for Inclusion Framework: Progress to Date QQI, AHEAD and the Disability Advisors Working Network (DAWN) Rethinking Assessment: Inclusive Assessment & Standards in a Dynamic and Changing World Conference. Dublin, Ireland.

Video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UG4Gvlt_vjA - Hyland, S., O’Neill, G.M., & Wolf, L.G (2023, November 11). What is ‘inclusive assessment’? Conversations with experts. Advance HE’s Assessment and Feedback Symposium 2023, Reading, UK.

Presentation: https://bit.ly/AfI-AdvanceHE

References

- Bain, K. (2023). Inclusive assessment in higher education: What does the literature tells us on how to define and design inclusive assessments? Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education, (27) https://doi.org/10.47408/jldhe.vi27.1014

- Evans, C. (2022). Inclusive Assessment The Equity, Agency and Transparency Framework (EAT) https://inclusivehe.org/inclusive-assessment/

- Henning, G. W., Baker, G. R., Jankowski, N. A., Lundquist, A. E., & Montenegro, E. (Eds.). (2022). Reframing assessment to center equity: Theories, models, and practices. Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003446729

- Hockings, C. (2010). Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: A synthesis of research. EvidenceNet, Higher Education Academy. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/inclusive-learning-and-teaching-higher-education-synthesis-research

- Kneale, P., & Collings, J. (2015). Developing and embedding inclusive assessment: Issues and opportunities. In W. Miller, J. Collings, & P. Kneale (Eds.), Inclusive assessment. Pedagogic Research Institute and Observatory (PedRIO). https://oro.open.ac.uk/42630/1/PedRIO%20Paper%207.pdf

- Kremmel, B., & Harding, L. (2020). Towards a comprehensive, empirical model of language assessment literacy across stakeholder groups: Developing the language assessment literacy survey. Language Assessment Quarterly, 17(1), 100–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2019.1674855

- Ling, T. Y., Yuen, L., Loo, B., Ling, W., Prinsloo, C., & Gan, M. (2020). Students’ conceptions of bell curve grading fairness in relation to goal orientation and motivation. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 14(1), Article 7. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2020.140107

- McArthur, J. (2016). Assessment for social justice: The role of assessment in achieving social justice. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 41(7), 967-981. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2015.1053429

- Morris, C., Milton, E., & Goldstone, R. (2019). Case study: Suggesting choice: inclusive assessment processes. Higher Education Pedagogies, 4(1), 435–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2019.1669479

- National Forum (2017). Expanding our understanding of assessment and feedback in Irish higher education. National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning. DOI: 10.6084/m9.figshare.4786300

- O’Farrell, L. (2019). Understanding and enabling student success in Irish higher education. National Forum for the Enhancement of Teaching and Learning. https://hub.teachingandlearning.ie/resource/understanding-and-enabling-student-success-in-irish-higher-education/

- O'Neill, G. M. (2019). Why don’t we want to reduce assessment? All Ireland Journal of Higher Education, 11(2). https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/415

- O’Neill, G., McEvoy, E., & Maguire, T. (2020). Developing a national understanding of assessment and feedback in Irish higher education. Irish Educational Studies, 39(4), 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2020.1730220

- Shukla, A., & Arora, V. (2023). A holistic approach to student empowerment and assessment of its impact on educational outcomes through psychological ownership. Studies in Higher Education, 48(8), 1315-1332. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2023.2197005

- Tai, J., Ajjawi, R., Bearman, M., Boud, D., Dawson, P., & Jorre de St Jorre, T. (2022). Assessment for inclusion: Rethinking contemporary strategies in assessment design. Higher Education Research and Development, 42(2), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2022.2057451

- University College Dublin, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Strategy and Action Plan 2021-2024. https://www.ucd.ie/equality/information/publications/edistrategyactionplan/

- Vander Schee, B. A., & Birrittella, T. D. (2021). Hybrid and online peer group grading: Adding assessment efficiency while maintaining perceived fairness. Marketing Education Review, 31(4), 275-283. https://doi.org/10.1080/10528008.2021.1887746

- Winstone, N. E., & Nash, R. A. (2016). The developing engagement with feedback toolkit (DEFT). Higher Education Academy. https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/developing-engagement-feedback-toolkit-deft

- Xu, Y., & Brown, G. T. L. (2016). Teacher assessment literacy in practice: A reconceptualization. Teaching and Teacher Education, 58, 149-162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.05.010