Activities: Simple and Complex

Prior to reading this page, have a look at What is Active and Collaborative Learning and Why Use it?

This webpage aims to:

- Support your planning for the activities used in these active and collaborative spaces, often described as ‘Active Learning Environment (ALE)’ spaces.

- Highlight some key questions around planning for and then teaching in these spaces.

- Present a template to help plan your activity.

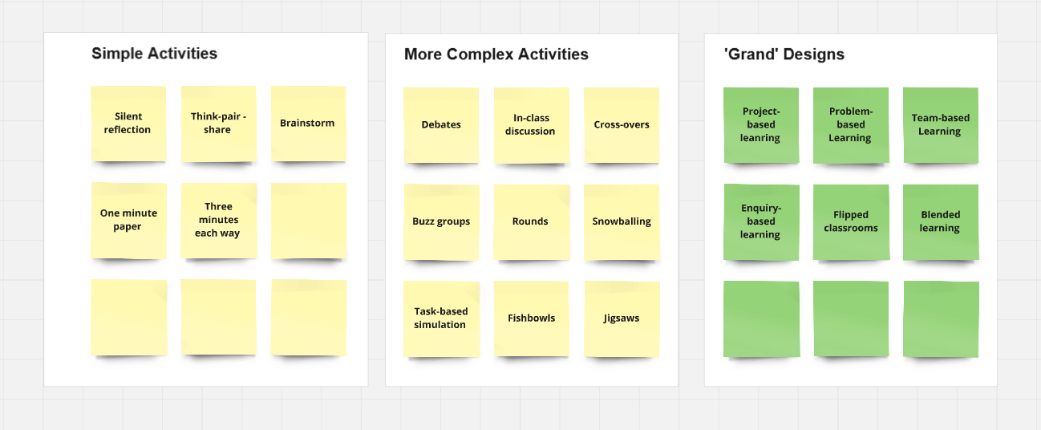

- Give examples of some commonly used activities, moving from activities that are easily set up to those that may require more complex planning. These activities may be part of a wider ‘grand design’ at the module or programme level.

- Highlight resources that suggest some additional activities.

Planning for Teaching in the Space

Giving thought to how you plan activities in these ALE spaces is key to its success. The following are 10 questions, based on common challenges identified by Baepler et al (2016), that may help you plan for a successful experience. This Template for Planning a Session in an Active Learning Space will also support documenting, sharing and reflecting on your plans. The template is linked with the following series of questions.

To prepare for teaching in an ALE, visit the space in advance, if possible, observe colleagues teaching in this space beforehand. Observations help understand teaching techniques, movement, and technology use. Videos, like those from the University of Toronto and the University of Minnesota, also offer insights into utilising ALEs effectively for interactive learning

- University of Michigan, Engineering

- Mayes-Tang, Mathematics Department (1st Year CALEulus): University of Toronto

Successful collaborative activities need to start well. Here are some examples of ‘warm up’ activities that could be used in the classroom or online. This webpage also focuses on ideas in particular that are ‘built on principles of equity and care that produce learning spaces in which all students can flourish.’

It's also important that the students themselves are prepared for an active and collaborative learning session. In this video Dr Anshu Suri, UCD Garfield Weston Assistant Professor of Marketing at the UCD Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School, talks about her approach for ensuring her students prepare for a session in advance.

These types of spaces are not designed for the traditional lecture; students in these spaces expect to be active. Due to their arrangement around tables while equipped with technology, these spaces are more inclined towards face-to-face interactions. In these spaces, long lectures are not suitable, but brief micro-lectures can help introduce topics, clarify concepts and address course updates.

One recommendation is to keep "micro-lectures" to a maximum of 20% of the time and intersperse them between activities. Lectures in your module that are pitched at ‘remember/understand’ (Bloom’s Taxonomy) may be best done in a lecture theatre or as a pre- or post-ALE session recording. Therefore, the ‘micro-lectures’ in the ALE space are often around ‘new concepts, clarifying misconception and dealing with general course administration’ (Baepler et al, 2016, p55).

Balance the small group, individual, and whole class activities during the session, as students can find too much small group work ‘tiresome’.

Collaborative and active learning, therefore, replaces the more didactic lecture. This can be more inclusive and provides students with opportunities to interact and learn from different perspectives.

For examples of hands-on activities used by UCD teaching colleagues in this approach, see the examples described in this video conversation with Dr. Mark Pickering, Lecturer/Assistant Professor in the UCD School of Medicine.

ALEs are designed to promote collaboration and active participation, moving away from traditional lecture-based methods.

More basic concepts that are easily understood by students may be more suited to pre-reading, video-recorded lectures or in-class student engagement with the material, such as students explaining content to other students. This allows for the more complex and ‘challenging’ concepts to be dealt with in the classroom. As you move around the room you are more likely to see where students are struggling with the content and this is where some mini-lectures or explanations are very appropriate.

You can enhance learning by balancing group activities with whole-class discussions, creating an inclusive environment where students can interact with diverse perspectives on the content. This way, the classroom experience becomes one of shared learning and encourages students to be engaged with the content during the class.

For an example of using video-recorded lectures as pre-class preparatory work for students, watch this extract from a short conversation with Associate Professor Neal Murphy, UCD School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering.

Moving from lecture to active learning, you may find it challenging to relinquish control, balance structure and flexibility and adjust to student interests. You will need to be flexible about how things progress during the class.

Plan for a strong sequence to your activities. When do you want students to have time for individual reflection and when do they need to discuss or work on a collaborative activity? Read the room. For example, are students flagging and starting to disengage in group activity? This may be a good time to bring them back to review their progress and ideas with the whole class. Having a series of questions or other activities prepared is always useful.

The following are examples of sequences for one or two-hour sessions for three different activity types:

|

Group Discussion |

Timing in Minutes (1 hour) |

Active learning with focus on students in pairs |

Timing in Minutes (1 hour) |

Problem-Based (PBL) |

Timing in Minutes (2 hours) |

|

One minute paper |

0-5 |

Mini-lecture/or instructions by staff |

0-10 |

Group Discussions (based on students’ research on previous PBL problem) |

0-20 |

|

Mini-lecture/or instructions |

5-15 |

In-class Poll Everywhere and Discussion of results in pairs |

10-20 |

Group Summary Presentations to Class (students) |

20-45 |

|

Group Discussion |

15 -30 |

Mini-lecture/or instructions by staff |

20-30 |

Mini-lecture by staff (based on gaps in knowledge) |

45-60 |

|

Group Presentation to Class (students) |

30-45 |

Think-Pair-Share |

30-50 |

Break |

60-70 |

|

Summary of class findings by staff and next steps |

45-55 |

Summary of class findings by staff and next steps |

50-55 |

Group Brainstorm of new PBL problem presented |

70-90 |

|

Mini-lecture/or instructions by staff |

90-110 |

While initially difficult, giving attention to how you sequence the session can lead to deeper, more varied questions and engagement by students. Active learning requires preparation but must be open to being changed as students engage in the learning.

You can mitigate student scepticism about ALEs by discussing the layout and collaborative learning benefits early in the course. Connect the in-class activities to other important skills, such as problem-solving and group work, that students will need both for academic success and employability.

Sharing research on improved learning outcomes, and better performance on exams taken in ALEs can help reassure students. Where relevant, you can also refer to past student experiences, demonstrating the space's effectiveness. Referencing teamwork-focused methodologies like Team-based Learning in module documentation reinforces the commitment to student-centred, skill-building approaches that benefit students both in class and after graduation.

Explain the value of and how your technical methods align with the space, while also “learning the room” by mastering the technology available. ALEs include, but are not limited to, such items as laptop projection, audio control, and varied lighting. Understanding how to manage multiple projection sources and ensure smooth interactions is key to expanding your teaching strategies.

It is advisable to go through quick guides and practice with the technology in advance. You may also find it helpful to practice with colleagues to simulate classroom scenarios for confidence and to enhance collaboration among students during lessons.

The collaborative tools available at UCD are critical to know, such as

- Google Workspace Apps

- Poll Everywhere

- Zoom Whiteboards (See also TEL Presentation by Eoin Campbell, School of Agriculture and Food Science)

Your School may have a licence for other active collaborative software tools, but you need to ensure that students are able to use these also and that you are able to support any technical queries from them.

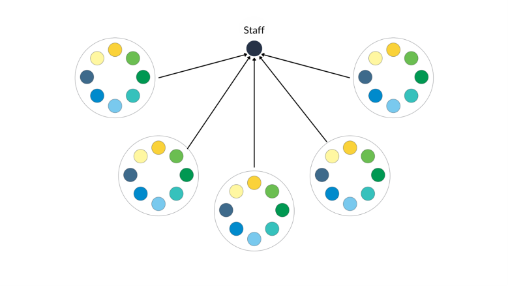

Unlike the traditional lecture, you are not at the top of the classroom. Positioning yourself in the middle or roving works better. You may need a wireless presentation ‘clicker’ or ‘pointer’ and a roving mic to facilitate this.

In ALEs, the seating arrangement can cause discomfort as you and the students may face each other’s backs, disrupting traditional eye contact and body language. You may wish to discuss the configuration with your students early in the module to reassure them that it is deliberate. Encouraging movement and circulation around the room further relaxes this space into a more informal and interactive environment. By moving around actively and covering all areas of the room, you can maintain participation, reduce distractions, and make the classroom inclusive to create a dynamic space for learning.

Teaching in large ALEs using the roving wireless microphones helps make communication clear and easy to hear. Larger ALEs in the new UCD O’Connor Centre for Learning will be furnished with an audience microphone. On the first day, introduce students to the microphones by having each student say something into the mic, and then pass it around, creating a brief moment of noise but helping students adjust to hearing their voices.

This practice relieves the students' uneasiness with using the mics, thereby minimising any initial discomfort or inhibition.

Familiarising the students with microphone use early in the module. Encourage active participation by your students in contributing questions and involvement in class activities.

Employ a range of strategies to recapture your students’ attention during activities. These strategies may involve:

- using a consistent phrase,

- web-based countdown timers,

- raising hands,

- utilising call signals

- indicator lights

Such methods assist in redirecting focus back to what you are saying and facilitate a smoother transition between group work and class discussions.

Try to also manage digital distractions, as technology can often divert students’ attention. To counter this, for example:

- establish rules about device use in advance,

- limiting laptops only to note-taking or certain tasks,

- suggests student blank their screws when not in use,

- incorporate tasks that require quiet time for students to reflect and help minimise the audio overload.

These strategies help students stay on task and prevent unnecessary distractions during collaborative work.

As in many evaluations of teaching, one of the key questions is: did you achieve the objectives that you set out for the session, such as, was there evidence of increased collaboration, enjoyment, learning of materials, etc.? This can be observed/recorded on video during the session, gathered by a quick in-class survey/poll, follow-up survey at the end of the module or at the end of a series of activities. Interviews and focus groups can help gather helpful data around student and staff perceptions and experiences of this approach. Other indicators of success can be students’ level of engagement, grades, developing a sense of belonging, etc. For more ideas, see the UCD Teaching & Learning resource on gathering evidence from students and colleagues (peers) on your teaching.

Unique tools that evaluate active and collaborative learning include:

- The Active Learning Inventory Tool (Peer Observation). This tool ‘was constructed to allow a trained peer observer to record the type, amount, length, and complexity of any observed active learning teaching behaviours. Each active-learning activity is recorded as a separate ‘‘episode’’ and asks the observer to comment on the quality of the classroom environment during the activity, the overall class atmosphere, and the perceived ease and skill of the instructor’ (Van Amburgh et al, 2007, p3)

- Student Questionnaire on Collaborative Learning: Razmerita and Kirchner (2014) developed a questionnaire to measure students' experience of collaborative learning. It comprised 18 questions, including collaboration online. Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree,) which explored:

- General collaboration: Enjoy collaboration with peers; Collaboration effect on learning and inspiration; Equal contribution of team members; Evaluation of end result of collaboration; Evaluation of overall satisfaction with collaboration

- Collaboration challenges: Social loafing; Lack of coordination; Lack of trust; Conflict; Different backgrounds of team members; Cultural differences in the team

- e-collaboration: Usage of e-collaboration tools; Prefer social interaction; Difficult to use; Not fun; No benefits; No need; Help to advance project ideas.

A revised version of this questionnaire was used by Lailiyah et al in 2021

- Students’ Sense of Belonging

For more on how you might explore students’ sense of belonging, see the UCD Belonging Project

References

Lailiyah, L., Setiyaningsih, L.A., Wediyantoro, P.L., & Yustisia, K.K. (2021). Assessing an effective collaboration in higher education: A study of students’ experiences and challenges on group collaboration. English Journal of Merdeka: Culture, Language, and Teaching of English, 6(2) 152- 162. doi:https://doi.org/10.26905/enjourme.v6i2.6971

15;71(5):85. doi: 10.5688/aj710585. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17998982/

Razmerita, L., & Kirchner, K. (2014). Social media collaboration in the classroom: A study of group collaboration. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 8658 LNCS, 279–286. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10166-8_25

Van Amburgh JA, Devlin JW, Kirwin JL, Qualters DM. (2007) A tool for measuring active learning in the classroom. American journal of pharmaceutical education. 71(5):85 DOI: https://doi.org/10.5688/aj710585

Examples of Activities

The following are

- some ‘simple’ activities, which can indeed be used in any classroom, are often described as ‘quick wins’ as they may require modest preparation time

- other activities that could be described as ‘more complex’ as they require more preparation time.

It may be that you wish to also scale up these activities as part of a more comprehensive module or programme design approach, in conjunction with other key stakeholders, and these require more consideration in the overall learning design, i.e. some ‘grand designs’. See examples of some activities that are more ‘grand designs’. All these activities require students to do something in class or in the surrounding space (behavioural), engage mentally with an activity (cognitive), and usually involve collaboration with peers (social) (Kozanitis & Nenciovici, 2023; Watkins, Carnell & Lodge, 2007). However, these three components may be weighted differently in different activities.

Each activity is considered under:

a) What it is, b) implementation ideas, c) technological implications in the space, and d) key references and resources.

What is it?

This is where you give students a few minutes to think about a problem or issue on their own.

Implementation ideas:

Ask them to write down their thoughts or ideas on a paper/tablet/computer. Keep the task specific. For example, ask them to write down the three most important, positive, expensive, etc. aspects of an issue. It is often useful to ask them to write on Post-its and then post them on, say, a notice board or the wall. Alternatively, ask them to share their ideas with their neighbour before moving into a discussion phase. Consider when could this approach be effectively used, i.e. in large groups; before a group is active/talkative; quieter groups; end of class summary/review; to get feedback from everyone…

Example:

An example of this is the One Minute Paper. In this example, Professor Suzanne Guerin explains how she uses this in a first year UCD Introduction to Applied Psychology is a large general elective module (n= 520 students): The students were given one minute to complete a paper on their understanding of the core features of research. Each student wrote their answers on a sheet of paper. At the end of the allotted time, the sheet of paper was then passed on to another student, who was asked to review and identify the most pertinent elements of their classmate’s definition. This in turn generated a wider class discussion of what students had highlighted as key features.

Technological implications in the space:

Software that uses notes, such as Poll Everywhere / Padlet, can help share comments afterwards in the class.

References and resources:

Hanh, N. T. (2020). Silence is gold?: A study on students’ silence in EFL classrooms. International Journal of Higher Education, 9(4), 153-160. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v9n4p153

Lees, H. (2013, August 22). Silence as a pedagogical tool. Times Higher Education. https://www.timeshighereducation.com/comment/opinion/silence-as-a-pedagogical-tool/2006621.article

What is it?

This is where every member of a group at a table takes a turn to answer a particular question.

Implementation idea:

Go around everyone in the group and ask them to respond. Try not to make the round too daunting by giving students guidance on what is expected of them. Keep it short! For example, try to avoid questions like "I want everyone to give their name and then identify one aspect of the course that they know nothing about but are looking forward to learning about”. In big rounds, students can be quite nervous, so make it clear that it's OK to pass and if people at the beginning have made your point, that concurrence is sufficient.

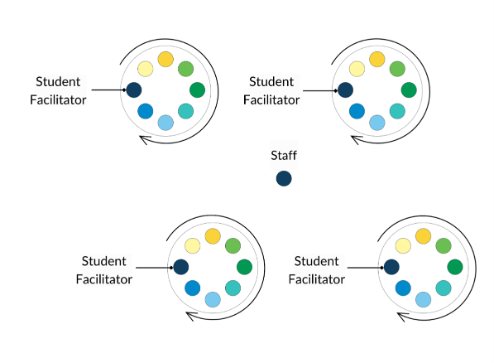

In large classes and active and collaborative learning spaces, the staff member can be substituted by a student facilitator at each table. Give consideration to when could this approach be effectively used, i.e. fairly small groups (20 or so); icebreakers; part of the winding-up of a session; to explore large/expansive topics…

Example:

A version of this is a ‘Grid question activity’ in which participants question each other on their out-of-class work. This approach was used in an Australia Regional University in a third-year undergraduate Arts and Education students (n=42) in an elective unit called ‘TESOL Methodology: Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages’. They describe that ‘Student 1 chooses a question from a grid handout and asks another student in the group. When the question is answered to the satisfaction of the group, the responding student then gets to choose the next question and respondent. This continues until the grid is completed.' The findings indicate greater class interaction, higher satisfaction ratings and better learning outcomes as a result of the strategies (Cruickshank et al, 2012).

Technological implications in the space:

Limited use, or no use of technology required in this activity.

References and resources:

Cruickshank, K., Chen, H., & Warren, S. (2012). Increasing international and domestic student interaction through group work: a case study from the humanities. Higher Education Research & Development, 31(6), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.669748

What is it?

Students are asked to speak in pairs uninterrupted for three minutes on a given topic and then they swap to listen to their partner.

Alternatively, a version of this can be Think-Pair-Share, where “students first THINK to themselves before being instructed to discuss their response with a person sitting near them (PAIR). Finally, the groups SHARE out what they discussed with their partner to the entire class and the discussion continues” (Lightner & Tomaswick, 2017)

Implementation idea:

Be strict with timekeeping. Your students might find this quite difficult at first, but it is an excellent way of getting students to articulate their ideas and also means that the quieter students are given opportunities to speak and be heard. The art of listening without interrupting, other than with brief prompts to get the speaker back on target if they wander off the topic, is one that many students will need to foster. This pair-work can then feed into other activities.

Consider when could this approach be effectively used, i.e. to develop relationships/ice-breakers; and encourage peer learning and interaction; the first step to increased participation and larger discussion…

Example:

As an example, In this video, Janet Rankin describes the think-pair-share active learning strategy. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fqrOxeL-fwk in Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA.

Technological implications in the space:

Limited use, or no use of technology required in this activity.

References and resources:

Lightner, J., Tomaswick, L. (2017). Active Learning – Think, Pair, Share. Kent State University Center for Teaching and Learning. https://www.kent.edu/ctl/think-pair-share

What is it?

In pairs, threes, fours, or fives students are given a small timed task which involves them talking to each other, creating a hubbub of noise as they work.

Implementation idea:

Their outcomes can then be shared with the whole group through feedback. Consider when could this approach be effectively used, i.e. to discuss more difficult or controversial issues; peer learning; get different perspectives on issues…

UCD example:

In this video, Sherry Ishak, Lektor in the UCD School of Languages, Cultures and Linguistics, talks about using these groups in her teaching to help give students confidence and make them feel comfortable so they are not afraid to speak. NB: Please ensure you have cookies enabled on your browser to view the video. If you cannot see the video, go to your cookie preferences and allow targeting cookies.

Further example:

For more on this in practice, have a listen to Stephen Brookfield (Association of College and University Educators), who described some questions to use in buzz groups. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_71ClQsQ8Iw

Technological implications in the space:

Outputs can be shared on a flip chart, on a Google doc on a large screen, in an online discussion forum, or otherwise as appropriate.

References and resources:

Avendo, D., Djunaidi, D., Marleni M. 2024 The influence of the buzz group discussion learning method on student learning outcomes in the english subject sdn 69 palembang, Esteem Journal of English Education Study Programme, 7 (1) DOI: https://doi.org/10.31851/esteem.v7i1.14117

Feldman, S. (2017). "Factors Influencing the Success of Buzz Group Discussion Method: Insights from an Educational Study." Journal of Educational Research and Practice, 37(2), 215–232. doi:10.1080/12345678.2017.1356789

What is it?

A quick way to create and share the whole group’s initial ideas on a topic, all ideas are accepted. Alternatively, it can be done at each table and shared with the whole group via a student facilitator.

Implementation idea:

Start with a question like "How can we..?" or "What do we know about ...?" and encourage the group to call out ideas as fast as you can write them up; perhaps use two scribes on separate boards if the brainstorming flows well. Make it clear that this is supposed to be an exploratory process, so set ground rules that:

- A large quantity of ideas is desirable, so everyone should be encouraged to contribute at whatever level they feel comfortable.

- Quick snappy responses are more valuable at this stage than long, complex, drawn-out sentences.

- Ideas should be noted without comment, either positive or negative - no one should say "That wouldn't work because...'" or "That's the best idea we've heard yet" while the brainstorming is in progress as this might make people feel foolish about their contributions.

- Participants should 'piggyback' on each other's ideas if they set off a train of thought, and 'logic circuits' should be disengaged, allowing for a freewheeling approach.

- The ideas thus generated can then be used as a basis for either a further problem-solving task or a tutor exposition.

Consider when this approach could be effectively used, i.e. to create an open, secure environment; stimulate creative free-thinking; problem-solving; generate diverse ideas…

Example:

This video ‘Brainstorming Video from IDEO U’ gives practical advice and an example of brainstorming in action with a group of students (‘Reduced footfall at the Zoo’).

Technological implications in the space:

Outputs can be shared on a flip chart, on a Google doc to a large screen, through Poll Everywhere (word clouds), in an online discussion forum, or otherwise as appropriate.

References and resources:

Hosam Al-Samarraie, Shuhaila Hurmuzan, (2018) A review of brainstorming techniques in higher education, Thinking Skills and Creativity, 27, 78-91, ISSN 1871-1871, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2017.12.002.

Staehle, M. (2018). Board 29: Work in progress: Learning from two little blue lines: Introducing biomedical engineering by reverse engineering a low-cost diagnostic device. Atlanta: American Society for Engineering Education-ASEE. Retrieved from

What is it?

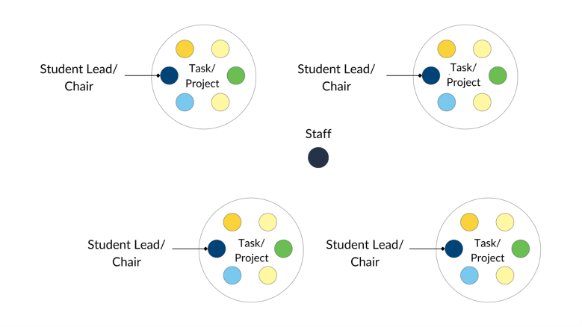

This is the term used to describe activities undertaken by groups of students working to a given brief. ‘Syndicate learning is a form of peer learning involving small groups of between 5 and 10 students working in semi-independent (tutor-less) groups towards the achievement of a collective goal or task’ (McKerlie et al, 2012). These groups aim to achieve a shared task rather than solving a problem, that is used in a problem-based learning approach.

Implementation idea:

These groups are student-led and therefore encourage them to have a chair, scribe, or other roles and to peer teach each other. They can be asked to undertake internet or literature searches, debate an issue, explore a piece of text, prepare an argument, design an artefact, or many other tasks. To achieve productively, they will need an explicit brief, appropriate resources, and clear outcomes. Specialist accommodation is not always necessary; syndicates can work in groups spread out in a large room, or, where facilities permit, go away and use other classrooms etc. If the task is substantial, the staff/tutor may wish to move from group to group or may be available on a 'help desk' at a central location. Outcomes may be in the form of assessed work from the group or produced at a plenary as described above.

Give consideration to when could this approach be effectively used, i.e. to develop ideas; assessment; developing interpersonal skills, and generic/transferable skills… The absence of staff in the groups can ‘enable students to take more responsibility for their own learning ‘ (McKerlie, et al, 2012).

Example:

One example of how this is implemented is described in the video conversation below by Dr Mark Pickering, Lecturer/Assistant Professor in the UCD School of Medicine, with his ‘fun’ 3D task of students developing some practical resources for teaching other students. They discuss, share and peer review this activity. NB: Please ensure you have cookies enabled on your browser to view the video. If you cannot see the video, go to your cookie preferences and allow targeting cookies.

Technological implications in the space:

Outputs can be shared at the table, on a flip chart, on a Google doc to a large screen, through Poll Everywhere (word clouds), in an online discussion forum, or otherwise as appropriate.

References and resources:

McKerlie, R. A., Cameron, D. A., Sherriff, A. and C. Bovill (2012) Student perceptions of syndicate learning: tutor-less group work within an undergraduate dental curriculum, European Journal of Dental Education 16 (2012) e122–e127 ISSN 1396-5883

What is it?

This technique, as the name suggests, builds ideas from one or two to an increasing number of students.

Implementation idea:

Start by giving students an individual task of a fairly simple nature such as listing features, noting questions, identifying problems, and summarising the main points of their last lecture. Then ask them to work in pairs on a slightly more complex task, such as prioritising issues or suggesting strategies. Thirdly, ask them to come together in larger groups, fours or sixes for example, and undertake a task involving, perhaps, synthesis, assimilation, or evaluation. Ask them to draw up guidelines, perhaps, or produce an action plan or assess the impact of a particular course of action. They can then feed back to the whole group if required. Give consideration to when this approach could be effectively used, e.g. working on complex tasks; introducing new ideas; peer learning; scaffolding for more effective learning.

Example:

This video gives a useful overview of the steps in this activity https://lf.westernsydney.edu.au/engage/strategy/snowball-technique/ (Western Sydney University)

Technological implications in the space:

Limited use, or no use of technology required in this activity.

References and resources:

Melbourne, S (2020) Active Learning: Using the snowball method to nurture critical thinking, University of West London.

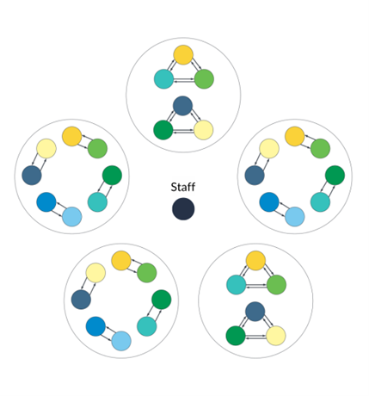

What is it?

A task to share those involved in central discussion, while an outside group listens

Implementation idea:

Ask for a small group of up to half a dozen or so volunteers to sit in the middle of a larger circle comprising the rest of the group. Give them a task to undertake that involves discussion, with the group around the outside acting as observers. Make the task you give the inner circle sufficiently simple in the first instance to give them the confidence to get started. This can be enhanced once students have had practice and become more confident. After a suitable interval, you can ask others from the outer circle to replace them. Some students will find it difficult to be the focus of all eyes and ears, so it may be necessary to avoid coercing anyone to take centre stage (although gentle prompting can be valuable).

A 'tag’ version can also be used, with those in the outer circle who want to join in gently tapping on the shoulder of someone in the middle they want to replace and taking over their chair and chance of talking. Alternatively, it can be very effective to give the observers in the outer group a specific task to ensure active listening. For example, ask them to determine the three key issues or conclusions identified by the inner group. It is then possible to swap the groups round and ask the new inner group to evaluate the conclusions identified by the first group. Fishbowls can work well with quite large groups too.

Consider when could this approach be effectively used: May be useful for managing dominating students (permission to be the centre of attention for some time); gives less vocal students the opportunity for undisturbed “air-time”; ways of getting feedback from buzz groups to class…

Example:

This video gives a good example of the steps to use in a fishbowl (TeachLikeThis (2024)

Technological implications in the space:

Limited use, or no use of technology required in this activity.

References and resources:

TeachLikeThis (2024) How to do a Fishbowl - TeachLikeThis

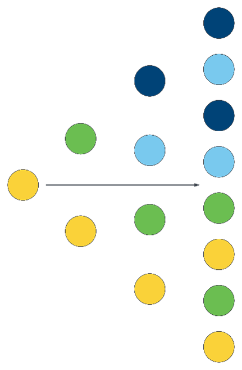

What is it?

A technique to divide up groups and then re-divide to support interaction between the groups.

A version of this is the Jigsaw approach:

‘each student of a “Home” group (a small group of students) chooses or is allocated a sub-topic related to the main topic to research. All the students from different “Home” groups with the same sub-topic assemble together to form an “Expert” group, where they research, discuss, and specialize in the given sub-topic. After mastering the sub-topic, the student returns from the “Expert” group” to the "Home" group and teach their allocated sub-topics to ensure holistic understanding of the main topic to the group members during the activity. Therefore, each student in the “Home” group serves as a piece of the topic's puzzle. Each part must work together and fit in perfectly to complete the whole jigsaw puzzle’ (Jeppu, Kumar, & Sethi, 2023, p2)

Implementation idea:

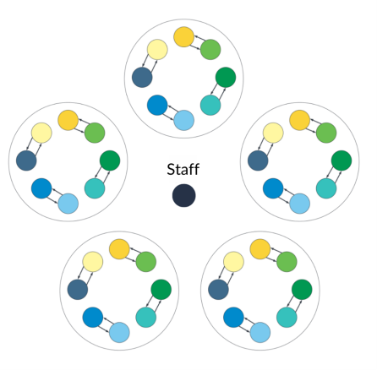

Often we want to mix students up in a systematic way so they work in small groups of different compositions. You can use crossovers with large groups of students, but the following example shows how this method would work with twenty-seven students.

Prepare as many pieces of paper as you have students, marking on them A1, A2, A3, B1, B2, B3, and so on (this combination is for creating triads). If you want to create groups of four students add A4, B4, etc. (You can do this as a header on hand-outs.)

When you are ready to have the students go into smaller groups, get them to group themselves with students who have the same letter as themselves: AAA, BBB, CCC, and so on for one group exercise. For a second exercise, ask the students to work with people who have the same number as themselves: 111, 222, 333. A third exercise will have students in triads where none of the students can have a matching letter or number: e.g. A1, D2 F3. This will allow you to get students to crossover within groups, so they work with different people on each task in a structured way. This technique also cuts down on the need to get a lot of feedback from the groups because each individual will act as a rapporteur on the outcomes of their previous task in the last configuration. As with snowballing or pyramids, you can make the task at each stage slightly more difficult and ask for a product from the final configuration if desired. Crossovers are useful in making sure everyone in the group is active and also help to mix students outside their normal friendship, ethnic, or gender groups.

It takes a little forethought to get the numbers right for the cohort you are working with (for example, you can use initial configurations of four rather than three, so that in stage two they will work as fours rather than triads). If you have one person left over, you can just pair them with one other person and ask them to shadow that person wherever they go. Give consideration to when this approach could be effectively used, i.e. to break up small, well-established groups from forming and reforming, other methods for mixing groups up: arrange themselves according to height/month of birth/county …..

Technological implications in the space :

In the Jigsaw approach access to a computer or laptop may be needed for researching the topic

References and resources:

Jeppu, A.K., Kumar, K.A. & Sethi, A. (2023) ‘We work together as a group’: implications of jigsaw cooperative learning. BMC Medical Education 23, 734. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04734-y

The activities below are some common approaches, in addition, however, these two comprehensive resources give a wide range of other ideas to use in these spaces:

- Liberating Structures gives a range of 35 activities that could be done online or face-to-face

- This other comprehensive Irish resource, Compendium of active learning strategies for student engagement by Ryan (2021) includes examples of:

Individual Activities

- Teacher Posed - Quick Write Prompt;

- Student Polling/Voting;

- Individual plus Group Quizzes;

- Strategic Pausing; PPPB (Pose, Pause, Pounce, Bounce);.

- Chain Notes/Post it Forum;

- Focused Listening;

- Knowledge Application Challenge;

- Making Connections and Approximate Analogies;

- Difficulties/Muddy Point;

- Clear Thinking/Blue Sky;

- Assigned Reading Exercise;

- Guided Paraphrasing Of Assigned Article;

- One Sentence Summary of a Key Concept;

- Background Knowledge Probe;

- Misconception Check;

- Classifying & Categorising Matrix;

- Assessment for Learning - Student Generated Assessment;

- RSQC2- Recall,

- Summarise, Question, Comment, and Connect; Periodic Learning Audit;

- The Devil’s Advocate Approach Discussion Inventory Following a Learning Audit;

- Minute Papers;

- Learning Portfolios;

- Learning Logs, Reflective Journals & Diaries; Module/Assignment Closure Strategies;

Partner Activities

- Turn and Talk;

- Think-Pair-Share;

- Think-Pair-Square-Share;

- Pair Peer Review of Assessment Task;

- Read and Explain Pairs

References and Bibliography

Anderson et al (2001) A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching and Assessing: A Revision of Bloom’s Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Longman, London, see also https://www.valamis.com/hub/blooms-taxonomy.

Baepler, P., Walker, J.D., Brooks, D.C., Saichaie, K., & Petersen, C.I. (2016). A guide to teaching in the active learning classroom: History, Research & Practice. Stylus.

Brown, S. ‘The Art of Teaching in Small Groups’, The New Academic Vol. 6, no. 1 (Spring 1997).

Brown, S. (2000). Institutional Strategies for Assessment, In, Assessment Matters in Higher Education: Choosing and Using Diverse Approaches. Buckingham: SRHE and Open University Press. Pp3-13.

Davies, P. (2001) 112 - Active Learning on Seminars: Humanities. SEDA

Healey, M. and Roberts, J. (eds.) 2004. Engaging students in active learning: case studies in geography, environment, and related disciplines, Cheltenham: University of Gloucestershire, Geography Discipline Network and School of Environment.

Liberating Structures - https://www.liberatingstructures.com/ls-menu/

McCabe, A. and O’Connor, U. (2014) ‘Student-centred learning: The role and responsibility of the lecturer’, Teaching in Higher Education, 19(4), pp. 350–359. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2013.860111

Petersen, C.I. and Gorman, K.S. (2014), Strategies to Address Common Challenges When Teaching in an Active Learning Classroom. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2014: 63-70. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20086

Prince M. (2004) Does active learning work? A review of the research. J Eng Educ 93: 223–231, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2168-9830.2004.tb00809.x

Wimpenny, L., & Savin-Baden, M. (2013) Alienation, agency and authenticity: A synthesis of the literature on student engagement. Teaching in Higher Education, 18 (3): 311-326.

(Note many of the resources in this webpage were adapted from: Jennings, D. 2022. Integrating activity to enhance learning: Quick wins in-session and online. UCD Teaching & Learning, UCD, Ireland)