Grand Designs

‘Grand’ Designs for Collaborative, Group and Team Work

Some activities in the active and collaborative learning spaces can be introduced easily by a lecturer/staff/student using these spaces, i.e. think/pair/share, group discussions, etc. (See examples of these in the simple to complex Activities webpage). However, to maximise the use of the space and resources required, and to build on the students' group and teamwork skills in this space, some designs require more module and/or programme oversight.

These designs, similar to the resulting learning experiences for students, usually require more stakeholders to sit around the table to plan the design. Stakeholders can include, for example, programme staff, students, educational technologists, educational developers, library staff, other professional staff and external stakeholders.

As a result, these enhancements can also be slower to develop but have more impact on the efficiency and effectiveness of the learning in this space and across the programme. The competencies gained from some of these designs also align with UCD’s development of student skills for work-integrated learning/employability and for some of the competencies required for education for sustainability. They also align with the objectives identified in UCD’s Strategy to 2030: Breaking Boundaries.

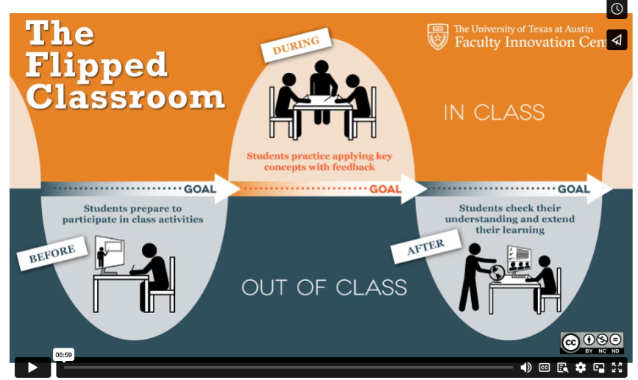

They can often be part of a design process that puts a different emphasis on the blend and sequence of face-to-face and online activities, such as the Flipped Classroom Approach (Seery, 2024; see also Al-Samarraie et al, 2020) or other Blended Learning approaches (UCD T&L, 2024).

Common characteristics of these overlapping approaches are:

- Students usually work in groups (within and/or outside of class),

- A high degree of student-centred learning,

- Use of complex, often real-life issues/examples,

- Students develop a range of transferable skills, such as problem-solving, team-working, critical thinking, and information-retrieval skills.

Some general advice on the benefits and guidance on group/teamwork and its assessment can be useful across many of these designs. Some ideas around how to assess different collaborative approaches are explored by Meijer et al (2020). In addition, some guidance for students from students is helpful in preparation for group work.

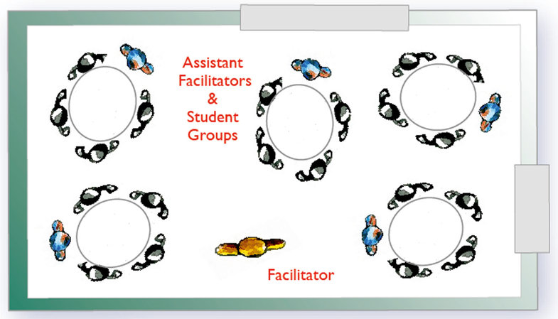

When used in a large class in an active and collaborative learning space, these approaches often work better when one of the students in each group is up-skilled to help keep the in-class activity on track, i.e. an assistant facilitator/chair. The lecturer (Facilitator) can then be like a roving tutor to ensure that they (assistant facilitators/chair) are keeping the activity on track. Other students in the group can also be given the responsibility to assist, i.e. time-keepers, note-takers, ‘live researchers’ using the computer, etc. For more on these roles see GROUP WORK AND ITS ASSESSMENT (UCD T&L 2024, p8)

See some common designs and their details below:

What is it?

Enquiry-based learning (or Research-Based Learning) is a student-centred learning approach where students research real-life issues or research questions. It can also be used as an umbrella term that includes other approaches such as problem and case-based learning. This method engages the students and fosters their problem-solving abilities and critical thinking originating from students’ curiosity on topics of interest, followed by research and an evidence-based conclusion (Tirado-Olivares et al., 2021). Unlike traditional classroom learning, this method encourages students to search for pertinent information about the topic under study, promoting curiosity and developing research skills. One approach suggests a 5E’s model of inquiry (Lederman, 2009):

- Engage: Students are engaged with a challenging situation or ‘wicked problem’, prior knowledge is activated, questions are provoked

- Explore: Students investigate the situation/problem, prior knowledge is challenged, new ideas are explored. This is often done in groups

- Explain: Students explain the situation/problem in their own words, new knowledge is gained and applied

- Elaborate: Students apply their knowledge towards new situations, knowledge is deepened and extended

- Evaluate: Students reflect on their knowledge and the learning process. This is often also where assessment occurs, and a new cycle kicks off with what was explored and uncovered previously, and is the foundation of a new situation or challenge to explore.

Implementation ideas

These are some examples of how this approach has been used in different contexts:

Connected Curriculum: a framework for research-based education (UCL)

Connected curriculum supports ‘the relationship between students’ learning and their participation in research, it also describes the connections to be made between disciplines, years of study and staff and students, to provide a more holistic educational approach. The term ‘research’ signifies very different kinds of activity in different subject fields. The Connected Curriculum initiative encourages individuals and teams within each discipline to think deeply about the nature and practices of their own research, and to invite students, including at undergraduate level, to learn through engaging in some of those distinctive practices. It also promotes interdisciplinary questions and challenges, encouraging both staff and students to critically question the nature of evidence and knowledge production across different subject fields in our digitally-mediated world’ (UCL 2025). The UCL webpage gives many resources and ideas around this research-based approach.

UCD Example: Arts and Humanities

Hands-on research in the humanities: Active learning through group project work . This video discusses the implementation of a module using an active learning curriculum design model, discussing the aims, method, and sustainability of the design. Group work was a major element of the module promoting engagement, collaboration, problem-solving and critical thinking. The talk was given by Associate Professor Naomi McAreavey, UCD School of English, Drama and Film at the UCD Teaching and Learning 2022 Symposium.

History Teaching Example

According to Tirado-Olivares et al. (2021), this study shows that inquiry learning can be used in history education. Students showed higher active participation through collaborative problem-based formative assessment enabled by certain digital tools, such as Poll Everywhere. Among these skills, the outcomes enhanced critical thinking, historical analysis skills, etc.

Chemistry Education Example

In 2024, Anwar et al. presented a paper detailing the investigation for implementing stepwise inquiry-based learning among chemistry undergraduate students. The activities were designed to promote hypothesis generation, experimentation, and analysis of results; this ties the activities to the scientific method while facilitating deeper understanding.

"Meet Your Researcher"

This adaptable induction activity, used at University College London (UCL), engages first-year students in learning through and about research. It aims to introduce students to the research culture of the discipline in general and the work of a research-active academic; to develop teamwork and project management skills; to develop students abilities to distil, synthesise and communicate key ideas and to develop their communication skills, including their ability to select appropriate language and media for a specified audience. Students meet researchers, discuss their work, and introspect on research processes, providing an active introduction to inquiry-based learning.

Technological implications in the space

Use of Poll Everywhere during the class session (see Tirado et al, 2021)

- Google Workspace Apps

- Zoom Whiteboards (See also TEL Presentation by Eoin Campbell, School of Agriculture and Food Science)

Key references and resources

- Carnell, B. Fung, D. (Eds) (2017) Developing the Higher Education Curriculum Research-Based Education in Practice. UCL Press. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787350878

- Hopkins & Mitchell, (2025) ‘Innovative pedagogies series: Research-based learning, taking it a step further’, HEA Academy

- Lederman, J.S (2009). "Levels of inquiry and the 5 E’s learning cycle model." National Geographic Science

- University of Melbourne (2025) Inquiry-based learning in higher education

What is it?

Problem-based learning (PBL) is a student-centred approach that actively engages students cooperatively in solving ‘messy’ real-world problems to gain knowledge and skills (Barrett, 2017). Unlike traditional lecture-based teaching, PBL promotes active learning in an open-ended scenario, building critical thinking, teamwork, and learning independence. Hence, students do not just learn the content of the subject but also acquire transferable communication and problem-solving skills. It works best when embedded in more than one module in a programme to allow students to become familiar with the approach, which can be different to the learning expectations in other modules. It uses a range of prompts to initiate discussion, such as short problems (unlike the more detailed information in case-based learning), scenarios, artefacts, images, art-work, etc.. It has a specific structure for how the process is carried out.

Implementation ideas

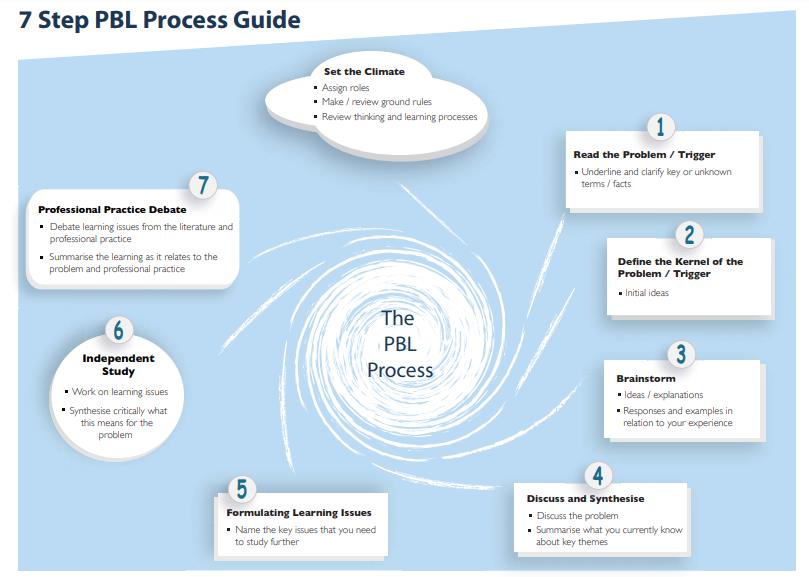

There are often three phases to a problem-based learning structure (or alternatively described as the 7 steps)

- The first in-class (online or in person) phase incorporates setting the climate for this approach and then steps 1-5 in the image below. This includes the teachers presenting clear problems for students to work on collaboratively. Students identify a core set of challenges, brainstorm and discuss potential solutions, and formulate learning goals for post-class work.

- The next phase (step 6), usually out of class, involves students doing independent research based on the learning goals and to build more background knowledge.

- The final phase (step 7): Usually back in the classroom, involves a debate of the shared findings from the students. This helps to integrate literature and practical insights to create comprehensive solutions. Different versions of this can be achieved, for example, all three phases (7 steps) can be condensed into one long PBL session/or day.

For a good overview of PBL:

- This Hull York Medical School video gives a good overview by staff and students. They note that it combines with lectures and clinical placements to ensure students develop the knowledge and skills they need to succeed.

- This introduction video from Maastricht University describes its four underlying core principles, that learning should be ‘collaborative, constructive, contextual and self-directed (CCCS)’. It gives some useful ideas for starting on the design.

UCD Examples

This comprehensive resource (Barrett & Cashman, 2010) on problem-based learning gives an account of seven different UCD case studies of its use in practice.

Technological implications in the space

The collaborative tools available in UCD’s suite of tools, such as

- Google Workspace Apps

- Poll Everywhere

- Zoom Whiteboards (See also TEL Presentation by Eoin Campbell, School of Agriculture and Food Science).

Key references and resources

- Barrett, Terry (2017) A New Model of Problem-based learning: Inspiring Concepts, Practice Strategies and Case Studies from Higher Education. Maynooth: AISHE

- Barrett, T., Cashman, D. (Eds) (2010) A Practitioners’ Guide to Enquiry and Problem-based Learning. Dublin: UCD Teaching and Learning. Funded by: Higher Education Authority (HEA) Ireland Strategic Innovation Fund

- Queens University (2025) Problem Based Learning

- Zhou J, Zhou S, Huang C, Xu R, Zhang Z, Zeng S, Qian G. Effectiveness of problem-based learning in Chinese pharmacy education: a meta-analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2016 Jan 19;16:23. doi: 10.1186/s12909-016-0546-z. PMID: 26787019; PMCID: PMC4719679.

What is it?

Team-based learning (TBL) is a ‘collaborative learning and teaching strategy that enables people to follow a structured process to enhance student engagement and the quality of student or trainee learning‘ (Lams, 2024). TBL encompasses individual assessments, team assessments, and some group exercises, whereby knowledge is put to practical use. TBL promotes engagement beyond normal classroom interaction and encourages teamwork, preparation, critical thinking, and an overall increase in students' classroom performance. This method enables deeper understanding and better learning outcomes through structured problem-solving activities.

Implementation ideas:

In this approach, students usually participate in a “Readiness Assurance Process” (Team-based learning (2025). It involves:

- Pre-Class Preparation: Assign readings or videos to prepare students for class, ensuring they are ready for the team assessment.

- Individual readiness: Start with an individual quiz on the material to check preparedness.

- Team readiness: Follow with a group quiz to encourage team collaboration and discuss answers.

- Application exercises: Engage students in solving complex, real-world problems in groups, reinforcing learning through discussion and problem-solving.

- Peer evaluation: Regularly assess individual and team contributions, promoting accountability within the group.

This video on Team-Based Learning gives an introduction for students on how the ‘Bradford School of Pharmacy have implemented a new curriculum from September 2012. Team-based learning is at the heart of the teaching and learning methods. The 2012 curriculum is designed by pharmacists, employers and other key stakeholders to achieve the patient-centred outcomes needed by pharmacists in practice’ (University of Bradford).

Technological University Shannon (TUS, 2026) have developed a suite of resources that guide students and staff in this approach (Note: technologies noted in these TUS examples may include software and tools that are unavailable in UCD):

- TBL facilitator guide: A guide for those wishing to run a TBL session

- Facilitating TBL – tools to succeed: pre-class preparation

- Facilitating TBL – tools to succeed: readiness assurance tests

- Facilitating TBL – tools to succeed: application exercises

- Technology for TBL

- Technology for TBL: peer evaluation

- Enhancing TBL with technology- 5 tips: online TBTeam Based Learning, similar to Problem Based Learning, is most impactful when it is adopted across the programme. This allows students and staff to build the necessary skills required and to become more familiar with these processes.

UCD Example of Team Work

A version of this approach was used and researched in UCD by Dr Arturo Gonzales in Stage 3 and Stage 4 Civil Engineering, Structural Engineering with Architecture, and Engineering Science Students. He describes it as:

‘A form of cooperative learning known as Team Game Tournament (TGT) is employed for this purpose. TGT enhances learning via the establishment of a tournament where the class is divided into teams that play against each other. The principle behind TGT is that the success of a team lies in the success of the individuals composing the team. Therefore, team mates help each other and study more than individually because they care for them and for the team. This variation of TGT was inspired by the UEFA ‘Champions League’.

Technological implications in the space

The collaborative tools available in UCD’s suite of tools, such as

- Google Workspace Apps

- Feedback Fruits (Peer review and Group Evaluation Tools)

- Zoom Whiteboards (See also TEL Presentation by Eoin Campbell, School of Agriculture and Food Science).

Key references and resources

- TUS (Technological University Shannon) (2026) Team Based Learning Centre for Pedagogical Innovation and Development

- Lams, 2024, Introduction to Team Based Learning, Youtube video

- Swanson, E., McCulley, L.V., Osman, D.J., Scammacca Lewis, N. and Solis, M. (2019). The effect of team-based learning on content knowledge: A meta-analysis. Active Learning in Higher Education, 20(1), pp.39-50

- Team-based learning (2025) Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching.

- UCD Teaching & Learning, (2024) Collaborative Teaching of Engineering and Architecture Students

What is it?

Project-Based Learning (PjBL) is a dynamic, student-centered teaching approach that involves students actively engaging in real-world and meaningful projects. On occasion, this approach can also be focused on a more specific practical skill. Unlike traditional teaching methods, PjBL provides room for learners to investigate challenging questions and complex challenges, leading to deeper understanding and the gaining of knowledge through extended inquiry and collaboration. This method emphasises critical thinking, creativity, and problem-solving, preparing students for professional and academic success.

Implementation ideas

To implement Project-Based Learning effectively, start with a well-defined project scope that aligns with learning objectives and student interests. The students are encouraged to brainstorm ideas and develop a project plan identifying the resources needed. Throughout the process, feedback will be provided regularly, and collaboration will be encouraged using structured group activities. Some elements of these formative assessments might include using project checkpoints or employing peer review to ensure students can see their progress. Culminate with some kind of presentation or showcase where students of every kind share their findings while reflecting on their learning experience.

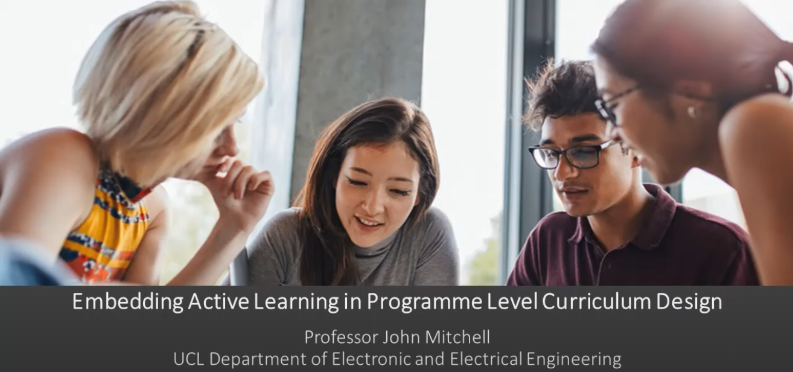

This keynote talk was delivered by Professor John Mitchell, UCL Department of Electronic and Electrical Engineering at the UCD Teaching and Learning Symposium 2022. Professor Mitchell discusses why and how active problem/project-based learning was embedded across 8 different departments, using the example of the Integrated Engineering Programme at UCL, also discussing the benefits and challenges of the implementation.

UCD Examples

"Healthy Eating, Active Living"

In this video, Nicola Dervan, Dietetics Special Lecturer and Practice Tutor in the UCD School of Public Health, Physiotherapy & Sports Science, discusses the active and collaborative learning elements in her module on the MSc. Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics program. The topic focus in this experience was "Healthy Eating, Active Living". She explains that this interdisciplinary project was in a practice placement module with students returning every Friday for a day of learning. The learning methodologies used project-based learning with a focus on developing critical thinking, clinical reasoning, and problem-solving skills. Nicola also mentions the use of peer learning activities such as peer review and group work. The activity was formally evaluated and student collaborative skills were enhanced. The ultimate goal is to enable students to work effectively as part of a team when they qualify. NB: Please ensure you have cookies enabled on your browser to view the video. If you cannot see the video, go to your cookie preferences and allow targeting cookies.

“The Paper Tower Challenge”

In this video, Professor Michael Gilchrist talks about the positive impact of this approach with a class of 320 first-year UCD Mechanical and Materials Engineering students. The students have been set a challenge to build a one-meter-tall tower that will hold one kilogram. The students work in teams and use only paper in the construction. The students and the lecturer elaborate in the video on their experiences of this approach.

Technological implications in the space

The collaborative tools available in UCD’s suite of tools, such as

- Google Workspace Apps

- Poll Everywhere

- Zoom Whiteboards (See also TEL Presentation by Eoin Campbell, School of Agriculture and Food Science).

Key references and resources

- Virtue, E. E., & Hinnant-Crawford, B. N. (2019). “We’re doing things that are meaningful”: Student Perspectives of Project-based Learning Across the Disciplines. Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning, 13(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.7771/1541-5015.1809

- Pengyue Guo, Nadira Saab, Lysanne S. Post, Wilfried Admiraal, A review of project-based learning in higher education: Student outcomes and measures, International Journal of Educational Research, Volume 102,2020,101586, ISSN 0883-0355,https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101586.

What is it?

Case-based learning (CBL) is an approach to active learning in which real-world scenarios or case studies are used to foster critical thinking, problem-solving, and application of knowledge. It is commonly used in Business and Law programmes. In CBL, students are presented with a detailed situation or problem, often from a specific field or industry and are tasked with analysing it, discussing possible solutions, and reflecting on the outcomes. This method encourages students to engage in inquiry-based learning, fostering deeper understanding and the development of practical skills.

Implementation ideas

Case-based learning (CBL) can be implemented when real-life scenarios, which are connected to the important matter of the course, are presented to students for analysis and discussion in groups. To enhance collaboration, students can work together using tools like Google Workspace for co-authoring documents, sharing data in Sheets, and creating presentations in Slides. Virtual meetings via Google Meet and Zoom can support group discussions, while Poll Everywhere allows for real-time feedback. Role-plays and reflective journals can further immerse students in their learning, allowing them to reflect on that learning and devise a solution.

Examples

Yale University (2021) describes and links to examples of case-based learning in different contexts, for example:

- Law – A case study presents a legal dilemma for which students use problem solving to decide the best way to advise and defend a client. Students are presented information that changes during the case.

- Business – Students work on a case study that presents the history of a business success or failure. They apply business principles learned in the classroom and assess why the venture was successful or not.

- Humanities - Students consider a case that presents a theater facing financial and management difficulties. They apply business and theater principles learned in the classroom to the case, working together to create solutions for the theater (Yale University (2021).

UCD Example

In this video, Dr. Anshu Suri, UCD Garfield Weston Assistant Professor of Marketing at the UCD Michael Smurfit Graduate Business School, shares her insights and experiences on teaching in active and collaborative learning spaces from her role in teaching digital retailing and customer experience management. She discusses her teaching methods, emphasising the use of case-based learning and simulations to prepare students for real-world business problems. She explains that students read cases beforehand and apply theoretical models in class, often in groups. Dr Suri also mentions the use of project-based learning, such as developing a business model and website, and the incorporation of design thinking. She shares advice on how others might use this approach in the future. NB: Please ensure you have cookies enabled on your browser to view the video. If you cannot see the video, go to your cookie preferences and allow targeting cookies.

Technological implications in the space

The collaborative tools available in UCD’s suite of tools, such as

- Google Workspace Apps

- Poll Everywhere

- Zoom Whiteboards

Key references and resources

Yan, Y., & Ottenbreit-Leftwich, A. (2023). Case-based learning: Consider and reflect teaching practices through teacher moments. TechTrends: Linking Research & Practice to Improve Learning, 67(6), 903-917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-023-00902-5

What is it?

The flipped classroom is an approach to blended learning where traditional classroom activities and homework are reversed. In this model, students first engage with new content outside the classroom, often through online videos or readings, and then use class time for interactive activities such as discussions, problem-solving, or collaborative work. This allows more time for active learning and personalised support from teachers during class time.

See associated video overview of flipped classroom from The University of Texas at Austin.

Implementation ideas

Flipped classroom implementation requires teachers to prepare some engaging pre-class material, like concise videos, readings, or podcasts, that let students learn core concepts at their own pace. Class time can then be used to apply that knowledge through active learning such as group discussion, peer teaching, problem-solving activities, and case studies, thereby facilitating deeper understanding and critical thinking skills. Furthermore, formative assessments, such as quizzes or interactive polls, will assist in determining how well the students understood the content and eliminate misconceptions. Closing reflection activities and feedback surveys at the end of class consolidate learning and inform future teaching strategies.

UCD Example

One example of how this is implemented is described in the video conversation below by Associate Professor Neal Murphy, UCD School of Mechanical and Materials Engineering. NB: Please ensure you have cookies enabled on your browser to view the video. If you cannot see the video, go to your cookie preferences and allow targeting cookies.

This is another flipped classroom case study, which used a pre-class quiz. It was implemented by Professor James Sullivan in UCD Chemistry in an elective module for stage 1 science students (CHEM10040 – The Molecular World) and for 2 years in a core module for stage 1 engineering students (CHEM10030 – Chemistry for Engineers). It was implemented to encourage engagement of the students with the work they were going to be carrying out during a particular session, before they arrived at the lab, and in this way change the practical sessions from a mostly-by-rote exercise to a far more planned and active learning exercise

Technological implications in the space

The collaborative tools available in UCD’s suite of tools, such as

- Google Workspace Apps

- Poll Everywhere

- Zoom Whiteboards (See also TEL Presentation by Eoin Campbell, School of Agriculture and Food Science).

Key references and resources

Suárez, C. A. H., Avendaño Castro, W. R., & Gamboa Suárez, A. A. (2022). Impact of B-Learning supported by the flipped classroom: An experience in higher education. Journal of Language and Linguistic Studies, 18(3), 119–129. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1379521.pdf

Kugler AJ, Gogineni HP, Garavalia LS. (2019) Learning Outcomes and Student Preferences with Flipped vs Lecture/Case Teaching Model in a Block Curriculum. American journal of pharmaceutical education 83(8):7044. doi: 10.5688/ajpe7044. PMID: 31831896; PMCID: PMC6900813.

For more on how and why to support building group work communities, the Equity Unbound webpages set out more on why to use collaborative approaches, some ideas to implement, and some useful warm-up activities to use. Their ideas in particular are ‘built on principles of equity and care that produce learning spaces in which all students can flourish.’

General References

Al-Samarraie, H., Shamsuddin, A., & Alzahrani, A. I. (2020). A flipped classroom model in higher education: a review of the evidence across disciplines. Educational Technology Research and Development, 68(3), 1017-1051. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-019-09718-8

Barrett, T., Cashman, D. (Eds) (2010) A Practitioners’ Guide to Enquiry and Problem-based Learning. Dublin: UCD Teaching and Learning Funded by: Higher Education Authority (HEA) Ireland Strategic Innovation Fund

Swanson, E., McCulley, L. V., Osman, D. J., Scammacca Lewis, N., & Solis, M. (2017). The effect of team-based learning on content knowledge: A meta-analysis. Active Learning in Higher Education, 20(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417731201

Thomas, J.W. (2000). A review of research on project-based learning. California: The Autodesk Foundation. http://www.bobpearlman.org/BestPractices/PBL_Research.pdf Accessed July 2021

Meijer, H., Hoekstra, R., Brouwer, J., & Strijbos, J. W. (2020). Unfolding collaborative learning assessment literacy: a reflection on current assessment methods in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 45(8), 1222–1240. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2020.1729696

Tormey, R. (2021). Rethinking student-teacher relationships in higher education: A multidimensional approach. Higher Education, 82, 993–1011.

Tsenn, J., McAdams, D. A., & Linsey, J. S. (2013). A Comparison of Design Self-Efficacy of Mechanical Engineering Freshmen, Sophomores, and Seniors. [Paper presentation]. American Society for Engineering Education 120th Annual Meeting, Atlanta, Georgia, United States. https://peer.asee.org/a-comparison-of-design-self-efficacy-of-mechanical-engineering-freshmen-sophomores-and-seniors

Uzunboylu, H., & Karagozlu, D. (2015). Flipped classroom: A review of recent literature. World Journal on Educational Technology, 7(2), 142–147. https://doi.org/10.18844/wjet.v7i2.46